Putting the “face” in Facebook: how Mark Zuckerberg is building a world without public anonymity

Facial recognition has matured sufficiently that it is cropping up in real-world applications with increasing frequency, as recent Privacy News Online stories attest. There’s one well-known company that is more active in this area than most, not least because it has access to more facial images than any other. It even has the word “face” in its name, and yet the key role of facial recognition in Facebook’s plans is still under-appreciated.

Facebook’s roll-out of facial recognition features has been taking place gradually over the last few years. It was as long ago as 2010 that the company introduced “tag suggestions“:

When you or a friend upload new photos, we use face recognition software – similar to that found in many photo editing tools – to match your new photos to other photos you’re tagged in. We group similar photos together and, whenever possible, suggest the name of the friend in the photos.

Later, Facebook expanded its “faceprints” database to include the profile pictures of people who were not tagged in any other photos. US Senator Al Franken was unhappy about this move, and in September 2013 wrote a letter to Mark Zuckerberg asking him to reconsider:

“Last July, as Chairman of the Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on Privacy, Technology and the Law, I held a hearing on the privacy implications of facial recognition technology; Facebook was one of our witnesses. As I said then, I was concerned by Facebook’s creation of what is likely the world’s largest privately held facial recognition database – without its customers’ express consent. The proposed expansion of this program is highly troubling, especially since Facebook has refused to promise its customers that it won’t share this program or its data with third parties in the future.”

Facebook declined to change its plans in the US, but had less luck in Europe. There, strict privacy laws meant that both Hamburg’s Data Protection Authority and Ireland’s Data Protection Commissioner found even the basic tag suggestions illegal. As a result, in 2013 Facebook deleted all the photo tagging facial recognition data it had obtained from users in the EU.

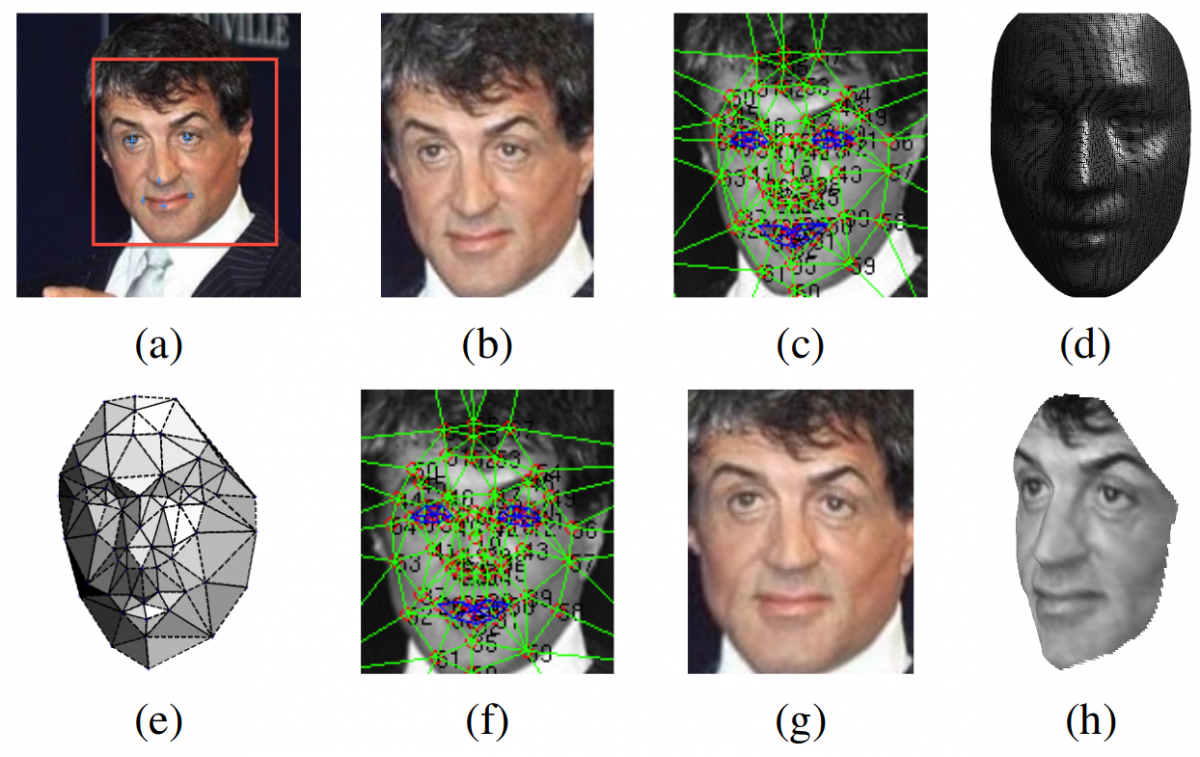

In 2014, Facebook researchers published a paper about a project called “DeepFace“. The paper’s title was “DeepFace: Closing the Gap to Human-Level Performance in Face Verification”, which is an academic way of saying that DeepFace was nearly as good as humans at recognizing faces. It achieved that by using a chunk of Facebook’s unparalleled facial dataset – four million facial images belonging to more than 4,000 identities – to train artificial intelligence software based on neural networks. The results were impressive: a claimed accuracy of 97.35% correct recognition of “Labeled Faces in the Wild ” – that is, real-life photos taken from Facebook pages. The system is also extremely efficient, as DeepFace’s lead engineer, Yaniv Taigman, told Science in 2015:

” ‘The method runs in a fraction of a second on a single [computer] core,’ Taigman says. That’s efficient enough for DeepFace to work on a smart phone. And it’s lean, representing each face as a string of code called a 256-bit hash. That unique representation is as compact as this very sentence. In principle, a database of the facial identities of 1 billion people could fit on a thumb drive.”

Since then, Facebook has continued to deepen and enrich its facial recognition technologies. An algorithm from the company’s artificial intelligence research group managed the seemingly impossible task of recognizing people 83% of the time even when their faces were not visible. The trick was to use associated characteristics that are visible in the photos uploaded to Facebook – things like hairstyle, clothing, body shape and pose. Other work by Facebook engineers, revealed in a 2014 patent application, tries to work out somebody’s emotions from facial expressions.

These continuing advances mean that Facebook has largely solved the facial recognition problem as far as the technology is concerned. It also possesses the largest face dataset, gleaned from its 2 billion users and their constant posting of photos of themselves, their family and friends. But there is one big threat to Mark Zuckerberg’s plans to apply facial recognition to Facebook’s unique collection of images ever-more widely: privacy laws. Although the US does not have federal legislation matching that of the EU, there is an important local law, as the Chicago Tribune explained:

“The Illinois Biometric Information Privacy Act [BIPA}, which passed in 2008, says no private entity can gather and keep an individual’s biometric information without prior notification and written permission from that person. The Illinois law is considered to be strict in that it allows for private citizens to sue companies that collect their data without meeting those requirements. Recently, the law has become the subject of a slew of lawsuits against tech giants Facebook, Google, Shutterfly and Snapchat, with consumers claiming their biometric information was handled illegally.”

Facebook tried to get the lawsuits brought against it over its tagging feature heard in California, where the use of biometric information is not restricted. But on a procedural issue, a California judge refused that request, and ruled that the case should be heard in Illinois, where BIPA applies. By an interesting coincidence, a couple of weeks after that ruling, an amendment was proposed to BIPA that would have excluded photo tagging from its reach. That would have been rather convenient for Facebook, which refused to confirm or deny that it had been involved in the move to get the amendment passed.

However, the BIPA amendment was not passed, so Facebook will need to defend its facial recognition systems in Illinois, in what will be one of the most important cases in this whole area. If Facebook loses, its business strategy could be jeopardized, as could those of many other Internet giants that also see facial recognition as a key future technology.

If Facebook wins, and is allowed to roll out more features and services based on increasingly-accurate facial recognition of billions of people, we will be moving towards a world without outdoor anonymity, just as Rick Falkvinge predicted on this site four years ago. But it won’t just be Facebook, Google and Microsoft that are scanning and identifying us everywhere we go in the physical world. The FBI launched a $1 billion facial recognition project back in 2012, the US Customs and Border Protection is planning to apply facial recognition to all airline passengers, including US citizens, boarding flights exiting the country, and key figures on Donald Trump’s Homeland Security team have strong links to the facial recognition industry. The technology will soon be ubiquitous. Enjoy the possibility of public anonymity while you can.

Featured image by Facebook Research.

Comments are closed.

What to do when we no longer can? Become hermits? Commit suicide?

Face-rec systems are by a large margin the single worst threat to privacy, and there are no reasonable countermeasures against it. No politicians in any part of the world is taking it seriously, here in Sweden even the Police has started connecting their outdoor CCTV cameras (which are fairly rare here, but still), their vehicle- and uniform mounted cameras to a central system with facial recognition.

Against Internet-based surveillance, there are a multitude of services and pieces of software to protect against different kinds of surveillance. AFK there are a few, that at best brands you as some kind of weird music style and/or sexuality (cvdazzle), and at worst is very likely to put you in jail as a robber, or at least be forced to take it off and be photographed by police, and put in a registry of suspects (balaclava).

So I ask again – What to do when face-rec is everywhere and anywhere? I don’t want to live in such a society, and neither of the options listed first is very attractive. This is a slow but clear emergency, that needs solutions. Quickly.