Here’s how Internet of Things malware is undermining privacy

The Internet of Things (IoT) is increasingly part of our everyday lives, with so-called “smart” speakers especially popular, But for all their undoubted technical merits, they also represent a growing threat to privacy, as this blog has reported before.

There are several aspects to the problem. One is that devices with microphones and cameras may be monitoring what people say and do directly. Sometimes users may not even be aware that there is a microphone present, as happened with Google’s Nest. Another is the leakage of sensitive information from the data streams of IoT devices. Finally, there is the problem summed up by what is called by some “Hyppönen’s law“: “Whenever an appliance is described as being ‘smart’, it’s vulnerable”.

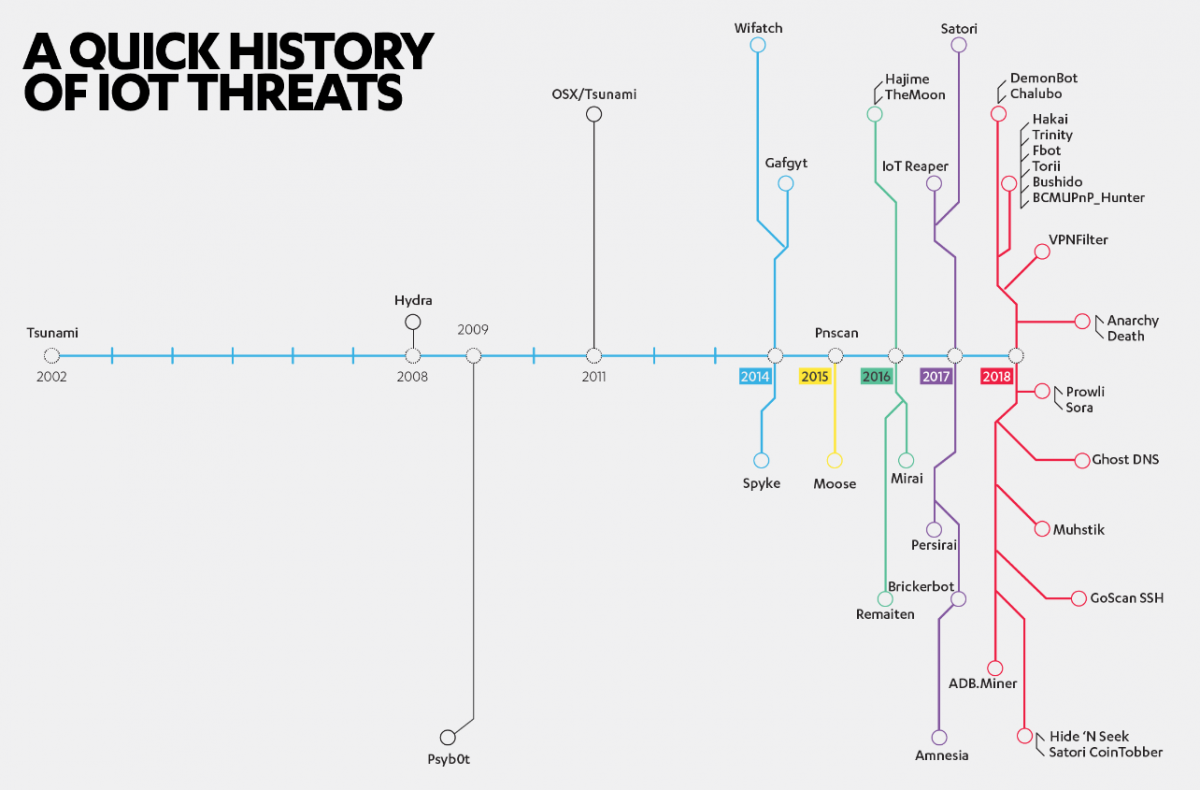

Mikko Hyppönen is Chief Research Officer at F-Secure, which offers security products and services. The company has released an interesting report that delves more deeply into the issue of people finding and using flaws in IoT devices. It’s a rapidly growing problem. In part, that’s because there are now billions of IoT products used in homes and connected to the Internet. One report estimates there are already seven billion IoT devices, a number predicted to triple by 2025. That huge pool of potentially vulnerable systems makes it worthwhile trying to break into them. It’s something that is reflected in the growth in threats directed at IoT devices. According to the F-Secure report, IoT threats went from one every few years in the early part of this century, to five in 2016 and 2017, and 19 in 2018. The rapid rise is also a reflection of the poor security of IoT systems:

thanks to the security problems commonly found in these devices, they present attackers with low hanging fruit to pick. According to F-Secure Labs, threats targeting weak/default credentials, unpatched vulnerabilities, or both, made up 87% of observed threats.

One popular tool for attacking IoT systems is Mirai. Originally, it would scan the Internet looking for exposed IoT systems. It would then try some 60 combinations of credentials in an attempt to gain control of anything it found. The open source nature of the code meant that people could and did build on the original malware, and increase its power. Within three months of the code’s release, the number of credentials it used had climbed to 500.

As the F-Secure report details, more recently there have been significant developments in IoT malware. For example, IoT_Reaper moved on from simply applying hard-coded passwords in the hope that they would unlock a system. Instead, it tries using 10 known vulnerabilities in HTTP control interfaces, most of them in publicly-facing IP and CCTV cameras, both of which have become common. Clearly the ability to access and control these cameras means that the privacy of people risks being seriously compromised. By contrast, the Hide N Seek malware, which builds on IoT_Reaper’s methods, prefers to install cryptominers, which generate virtual currency. Although the damage might seem indirect in this case, it’s important to remember that the devices are still under the control of criminals, and therefore pose a risk to privacy.

In 2018, VPNFilter appeared, which F-Secure speculates may have been developed by Russian-backed actors to attack Ukraine. As well as targeting Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) systems used in manufacturing and the maintenance of infrastructure, VPNFilter also attacks domestic routers:

At this point, the most vulnerable device in the home may be the one that connects most of the other devices to the internet. More than 8 out of 10 home and office routers were vulnerable to hacking, according to a 2018 study by the American Consumer Institute. This included five of the six major brands. It’s entirely possible that a router might have been hacked without the user even knowing it. With a technique called DNS hijacking, hackers can redirect traffic to a phishing website, where consumers may offer up a credit card number or login credentials.

A more general problem is that once an attacker is inside a home network, whether through vulnerabilities in a router or a camera, for example, it is possible that other IoT devices on it will be open to attack. Sometimes devices are abused not by external actors that have by-passed security measures, but by the very people who installed them. For example, the F-Secure report mentions how IoT devices are increasingly being used against victims of domestic abuse. The New York Times reported on this worrying trend last year, noting that “Abusers – using apps on their smartphones, which are connected to the internet-enabled devices – would remotely control everyday objects in the home, sometimes to watch and listen, other times to scare or show power. Even after a partner had left the home, the devices often stayed and continued to be used to intimidate and confuse.”

Even though poor security and abuse of IoT systems are a serious and growing problem, legal remedies are slow in coming. One of the most forward-looking moves comes from the UK government. Last October it released a Code of Practice for consumer IoT security, which contains a number of important ideas, notably that the security of personal data should be protected. But the Code of Practice is purely voluntary, which means that its impact will be limited.

Existing legislation may provide a more effective way of tackling IoT’s threat to privacy. As readers of this blog know, the EU’s GDPR law is proving to be a powerful weapon for defending personal data and tackling abuses. It may be that the GDPR can be used to curb some of the worst problems of IoT systems, at least in Europe.

Serious fines are available to the authorities under the GDPR – up to 4% of a company’s global turnover, wherever it may be located. That means that the security of IoT devices will probably improve in order to avoid liability under the GDPR – at least those from the mainstream manufacturers. Outfits producing cheap devices, for example in China, may be less worried by the threat of EU fines. Since it hardly makes sense to improve the design of a device for just one region, the hope has to be that pressure from the GDPR will cause the more responsible IoT manufacturers to pay more attention to privacy wherever they sell their products.

Featured image by F-Secure.