50 Key Stats About Freedom of the Internet Around the World

Almost every part of our everyday lives is closely connected to the internet – we depend on it for communication, entertainment, information, running our households, even running our cars.

Not everyone in the world has access to the same features and content on the internet, though, with some governments imposing restrictions on what you can do online. This severely limits internet freedom and, with it, the quality of life and other rights of the affected users.

Internet freedom is a broad term that covers digital rights, freedom of information, the right to internet access, freedom from internet censorship, and net neutrality.

To cover this vast subject, we’ve compiled 50 statistics that will give you a pretty clear picture about the state of internet freedom around the world. Dig into the whole thing or simply jump into your chosen area of interest below:

Digital Rights

Freedom of Information

Right to Internet Access

Freedom from Internet Censorship

Net Neutrality

The Bottom Line

Internet freedom is a broad term that covers digital rights, freedom of information, the right to internet access, freedom from internet censorship, and net neutrality.

Digital Rights

Digital rights refer to those rights that allow individuals to access, create, use, and publish digital media, or to access and utilize computers, other electronic devices, and telecommunications networks.

Digital Population around the World

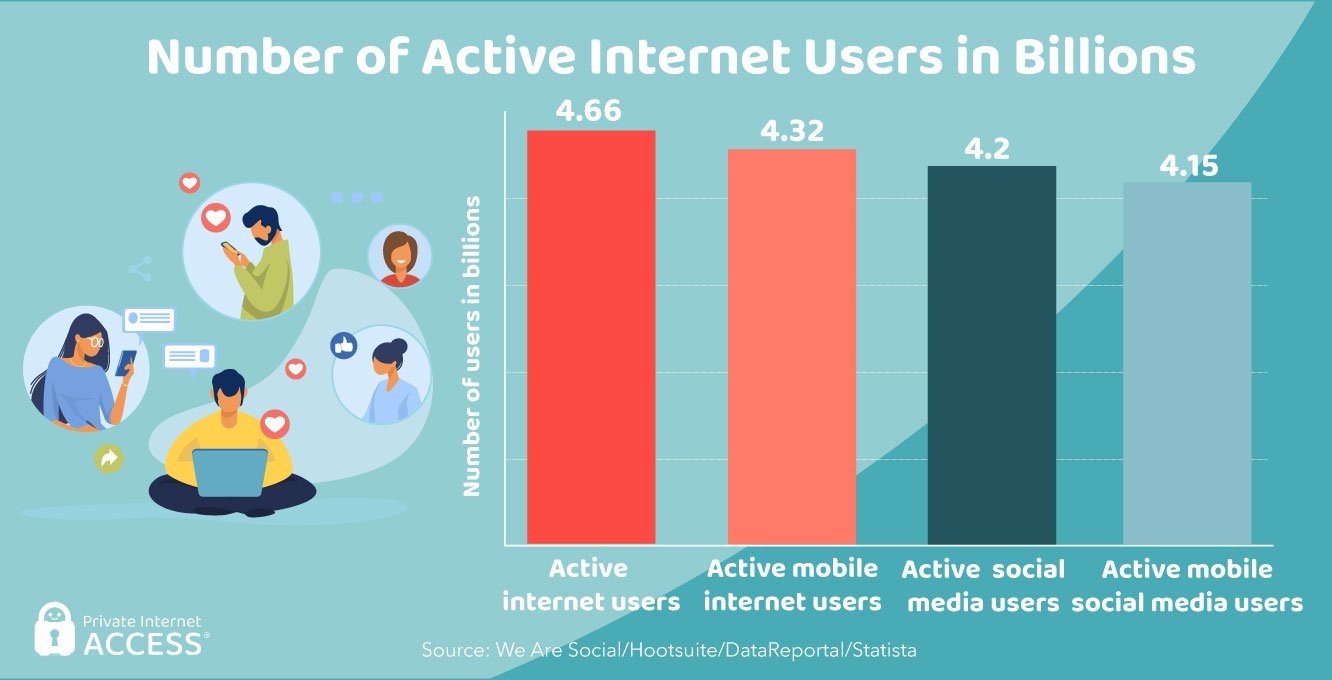

As of January 2021, there were 4.66 billion active internet users around the world, which is 59.5% of the entire world population. Among these, 4.32 billion or 92.6% were users actively using their mobile devices to access the internet.

In the same period, there were 4.2 billion active social media users, making up 90% of active internet users. Of this number, 4.15 billion or 98.8% used their mobile devices to actively participate on social media channels.

Growth of Global Digital Population

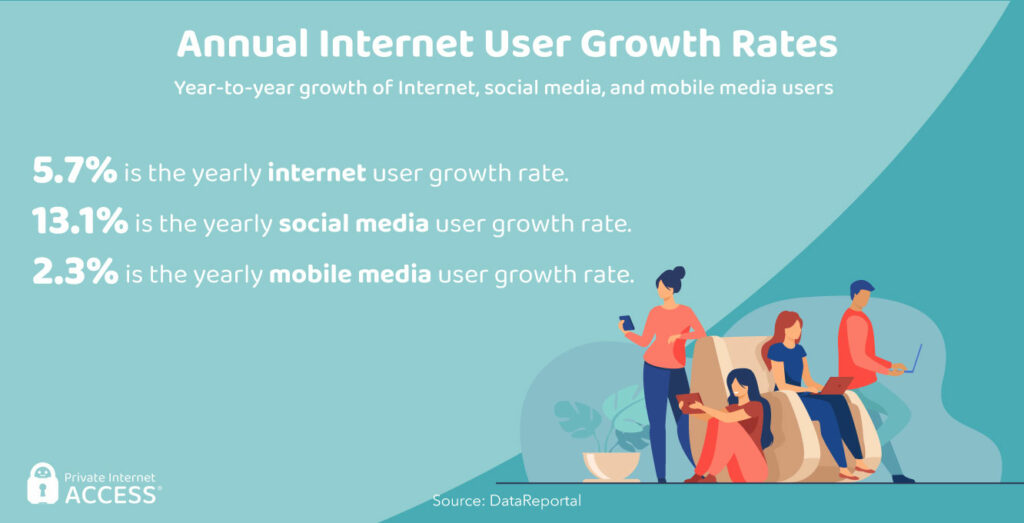

A lot has happened in the last year, and this is no less true for digital growth which saw some staggering numbers in the period between July 2020 and July 2021. The internet became richer by 257 million new users. This demonstrates an annual user growth rate of 5.7%, which is roughly 700,000 new users per day.

The same period saw an increase in the number of social media users by 13.1% percent, totalling 520 million new users. This means that each day, more than 1.4 million new people joined a social media platform.

The number of unique mobile users increased at a rate of 2.3% per year, growing by 117 million in the same year-long period.

Daily Computer and Internet Usage in EU

In 2019, 94% of young adults (ages 16-29 years) in the 27 EU countries accessed the internet daily. By comparison, 77% of the entire adult population of EU-27 (defined as ages 16-74) did the same.

The percentage of the entire adult population using a mobile phone or portable computer to connect to the internet was 73%.

In the same year, 92% of young adults used the internet over their mobile phones at home or work. In contrast, 52% used a portable computer this way for the same purpose.

Seventy-one percent of the adult population used a mobile phone in this case, versus 39% using a portable computer.

The percentage of young people in the EU using a computer (laptop or desktop) daily in 2017 was 14 points higher than for the adult population (62%).

Most People Are Concerned About Online Privacy

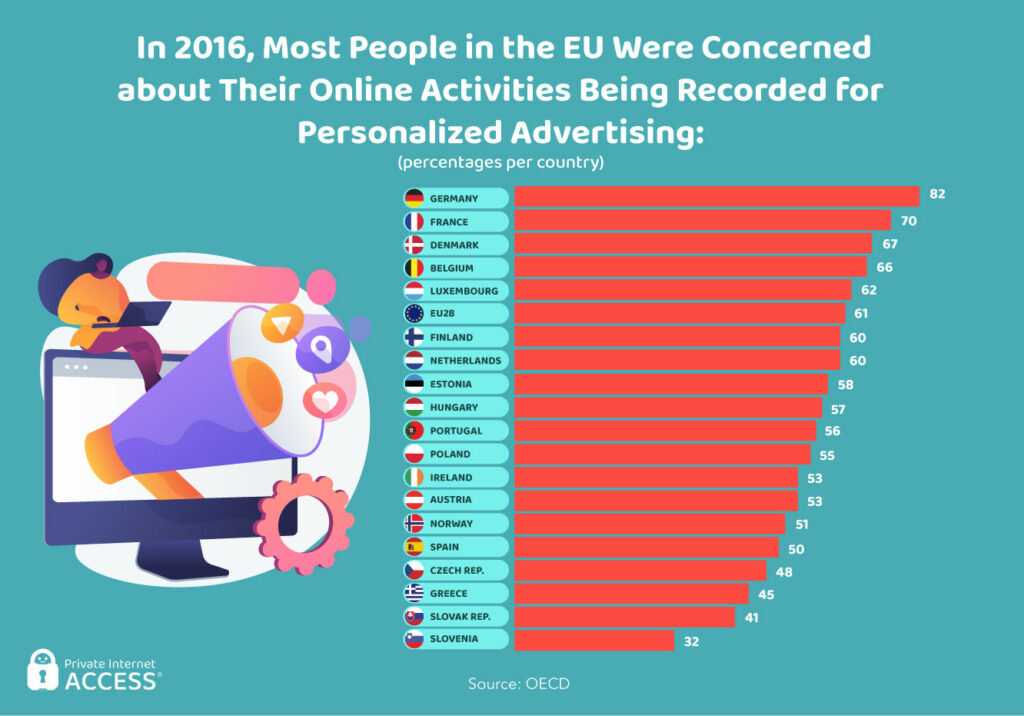

In 2016, most people expressed at least some degree of concern about their online activities being monitored for personalized advertising.

The concern was highest in Germany, where 82% of people said they cared about online privacy, followed by France at 70%, Denmark with 67%, Belgium at 66%, and Luxembourg at 62%.

Across the 28 EU countries (prior to the UK leaving), the total share of individuals concerned about their online privacy was 61%.

Tech Companies and Digital Rights Protections

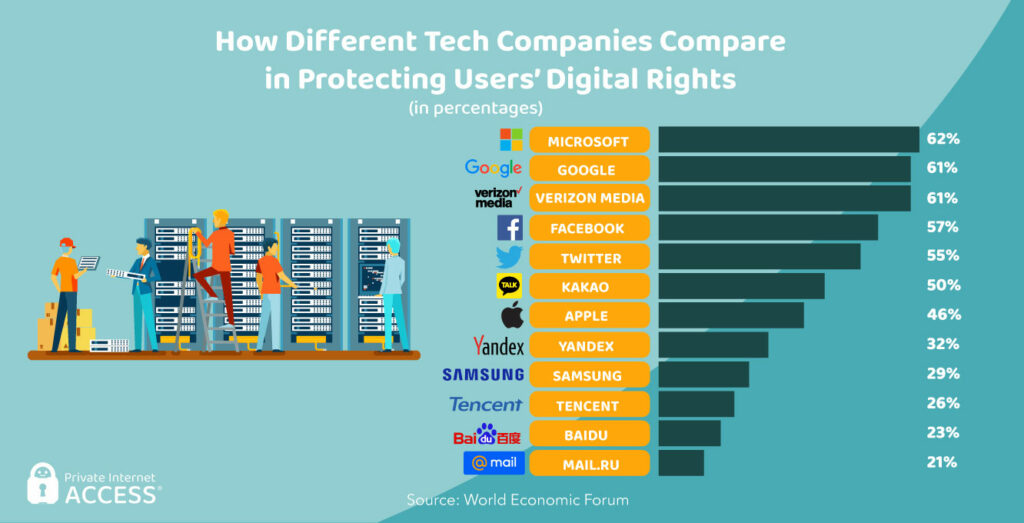

In 2019, Microsoft ranked as the best internet and mobile ecosystem company in terms of protecting users’ digital rights (scoring 62% out of 100 points), followed by Google (61%), Verizon Media (61%), Facebook (57%), and Twitter (55%).

Microsoft took over the leadership position from Google thanks to its strong governance and consistent application of privacy policies across the four services – Bing, Skype, OneDrive, and Outlook.

Only eight out of 24 of the world’s most powerful tech companies in the index scored 50% or above: Microsoft, Google, Verizon Media, Facebook, Telefonica, Twitter, Vodafone, and Kakao.

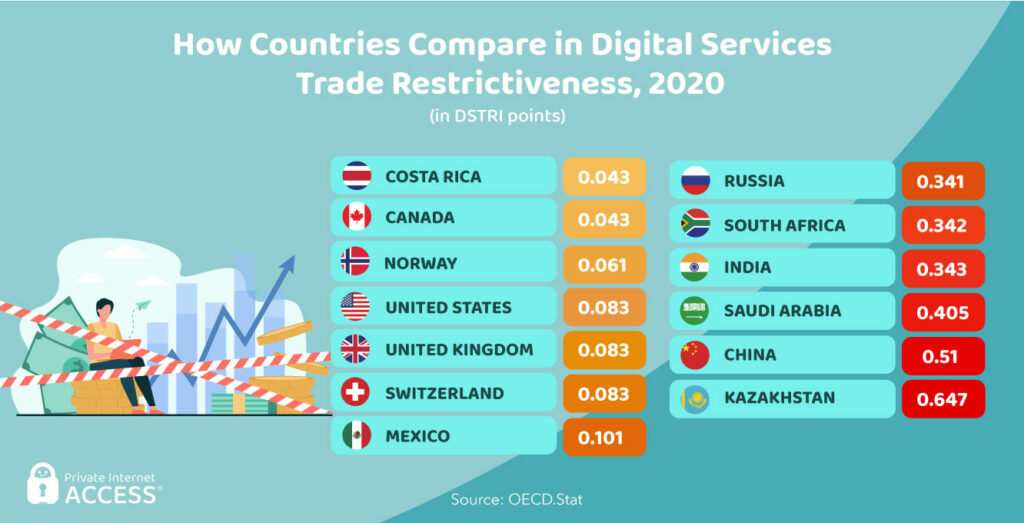

Which Countries Are the Least Open to Digital Trade?

Several countries impose significant restrictions on traditional trades (like legal, telecommunications, and financial services) that establish themselves digitally. Barriers imposed may include restrictions on online advertising, limitations on downloading or streaming, and mandatory usage of local software or technology transfers.

According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Digital Services Trade Restrictiveness Index (STRI), Kazakhstan scored as the place with the most barriers that affect trade in digitally enabled services in 2020.

Kazakhstan’s runner-up is China, which is followed by Saudi Arabia, India, South Africa, and Russia. Costa Rica, Canada, Norway, the US, UK, and Switzerland scored as the countries with the least constraints in this area.

For most countries, the results haven’t dramatically changed since 2014. The index slightly worsened for the most restrictive places: Kazakhstan, China, Saudi Arabia, India, and Russia, with the exception of South Africa, where it remained the same.

The situation slightly improved in the same period for Canada, Norway, and Mexico.

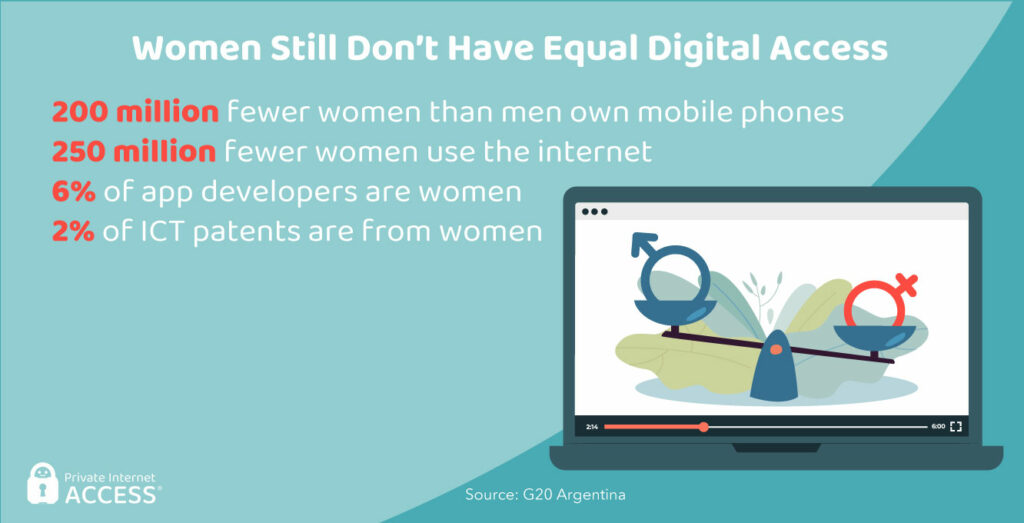

Challenging the Digital Gender Gap

As of 2015, an estimated 200 million fewer women (around 14% globally) than men owned mobile phones, 250 million fewer women than men were active internet users, and only 6% of app developers were women.

As per region, the gender gap was the widest in South Asia. It was the narrowest in Europe and Central Asia, even going in favor of women in some cases.

Surprisingly, the digital gender gap in terms of women as creators of technology is also evident in developed countries. In 2016 in the US, women accounted for 57% of all professional occupations, but only 25% of all computing occupations.

Only 2% of all information and communication technologies (ICT) patents are invented by female teams of inventors, compared to 88% of male teams’ patents.

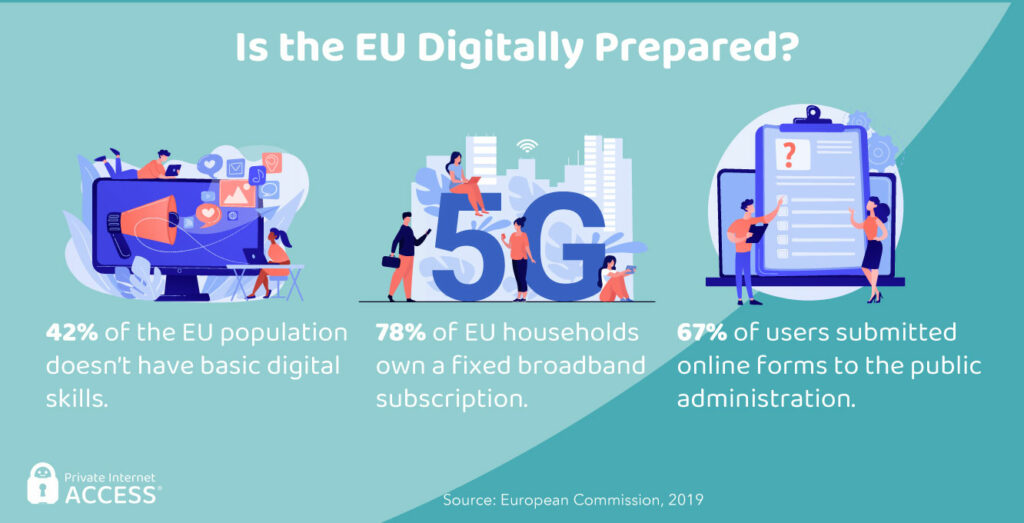

Digital Preparedness in the EU

The European Commission’s 2020 Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI) has shown that Finland, Sweden, Denmark, and the Netherlands lead in overall digital performance in the EU.

The DESI figures also indicate that as much as 42% of the EU population still lacks at least a basic level of digital skills. However, the share of EU households owning a fixed broadband subscription increased to 78% in 2019, up from 70% in 2014.

Although 4G networks cover just about the entire European population in 2019, only 17 member states had already designated the band spectrum for 5G.

The share of users submitting forms to public administration via the internet was 67% in 2019, which is a dramatic increase from 57% in 2015. The top-performing countries in this area were Estonia, Spain, Denmark, and Finland.

Freedom of Expression and Transparency Remain Inadequate

A handful of major internet, mobile, and telecommunications platforms have grown in such importance that they control access to information and public discourse. This is why it’s important that these companies are held accountable, providing maximum transparency about their practices.

The Ranking Digital Rights’s 2019 Corporate Accountability Index has shown that companies’ average overall performance in terms of freedom of expression increased only slightly between 2018 and 2019.

At 61%, Google had increased its overall freedom of expression score, but others not so much. Facebook did make some significant progress in its terms of service enforcement transparency. However, its freedom of expression score declined due to diminished transparency in terms of third-party and government demands (47%).

Facebook, Google, and Twitter all published more information about content removals due to terms of service enforcement than in the previous years. Microsoft published some information but less systematically.

Freedom of Information

Freedom of information or the right to information is the right granted to individuals and groups to publish and access information held by public bodies.

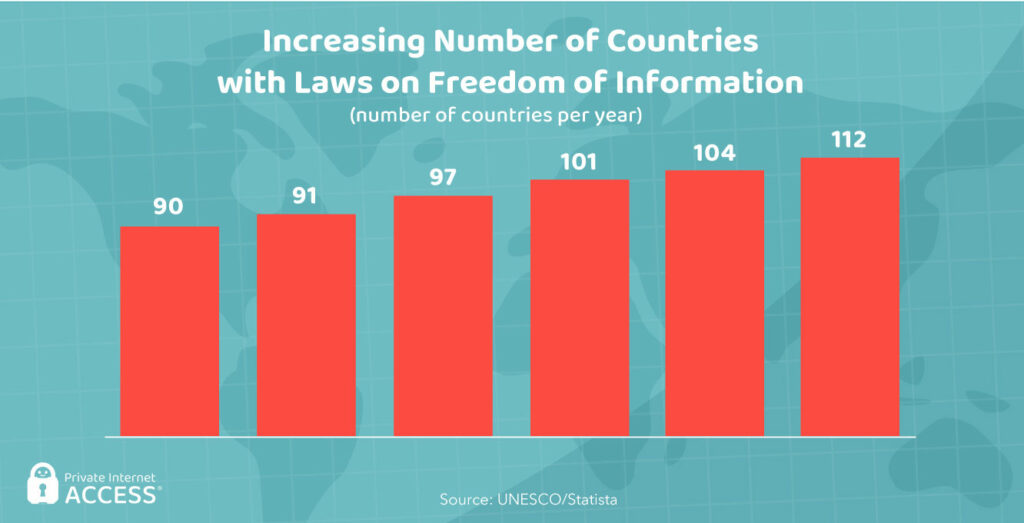

Freedom of Information Laws Welcomed in More Countries

The first country in the world to pass some form of freedom of information legislation was Sweden, which adopted its Freedom of the Press Act in 1766. Freedom of information is considered so important that in 2015, the United Nations dedicated a whole day to it – September 28 – which became known as the Access to Information Day.

An increasing number of countries are adopting the Freedom of Information laws. The most significant growth was recorded in 2016, when eight new countries enacted them – bringing the total number of countries with freedom of information laws to 112.

Freedom of Information Requests in the United Kingdom

In 2019, the central UK government received a total of 49,439 Freedom of Information requests across all monitored bodies, a 1% decrease from the year before. The Government responded on time in 93% of the cases, a 2% increase compared to 2018.

Of the total number of requests, the Government granted 43% in full, withholding 39% in full, roughly the same levels as in the year before.

More than two-thirds of all requests (33,954) were at Departments of State. Of these, the Department for Work and Pensions, Ministry of Defence, Ministry of Justice, and Home Office got the highest number of requests for the sixth consecutive year.

Freedom of Information Requests from the UK Ministry of Justice

In 2020, the UK Ministry of Justice received 809 information requests, of which 726 were under the Freedom of Information regulation, and 83 under the Environmental Information Regulations (EIR).

The Ministry completed 712 requests on time. It supplied full information in 592 or 73% of the cases, partial information in 103 or 13% of the cases, refusing 30 or 4% of the requests for information.

The highest number of information requests came from the press and media (282), followed by members of the public (205), and companies or commercial organizations (175).

Freedom of Information Requests from the UK Financial Ombudsman

In the 2020-2021 period, the UK Financial Ombudsman received 455 requests for information under the country’s Freedom of Information Act.

It provided full information in 36% of cases, partial information in 12% of requests, while it refused information in 43% of the cases. In 9% of the cases, the information wasn’t held by the Ombudsman.

Out of the total number of requests received in the 2020-2021 period, 86% of them were responded to on time.

Freedom of Information Requests in Australia

Granted by the Freedom of Information Act, there were 41,333 requests for copies of documents held by the Australian Government and its agencies in the 2019-2020 period. This number is higher than in the previous 10 years.

Of this number, 33,584 or 81.3% were requests for personal information, which is also the highest in the ten-year period.

In terms of responses to the requests, 13,727 or 33.21% were granted in full, 11,221 or 27.15% in part, while access was refused in 4,410 or 10.67% of the cases.

Decline in Media Freedom Worldwide

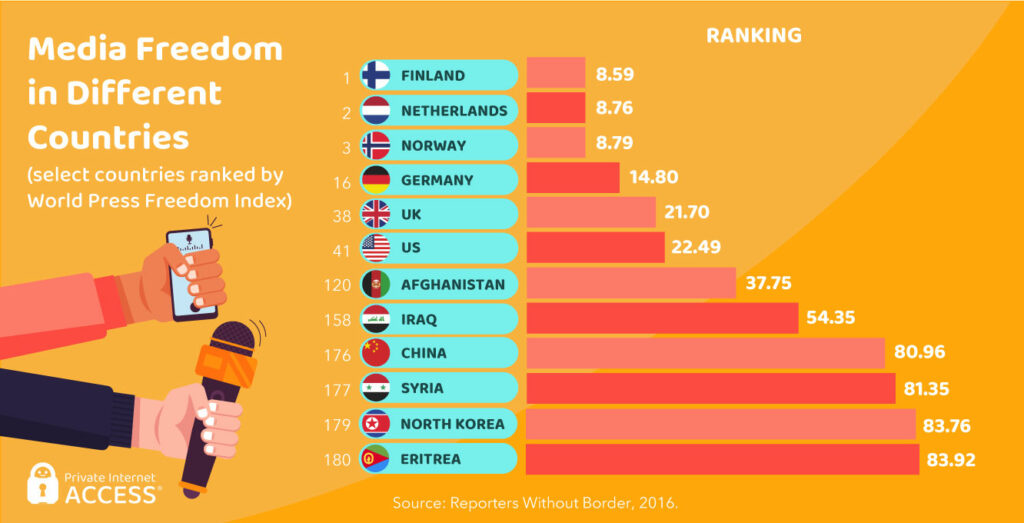

According to the 2016 World Press Freedom Index by the NGO Reporters Without Borders (RSF), the year marked a disturbing decline in respect to media freedoms, both at the global and regional levels.

In 2016, Finland, the Netherlands, and Norway were the best countries in terms of freedom of the press. The worst places in this field were Eritrea and North Korea, which ranked last among 180 countries. Syria wasn’t as bad as these two, but was still on a low, 177th place. China ranked better than Syria but by less than one point.

Germany was in 16th place, while the UK ranked 38th. The US was well below these two countries, assuming a very low position among developed nations – 41th.

Impact of Covid-19 on World Press Freedom

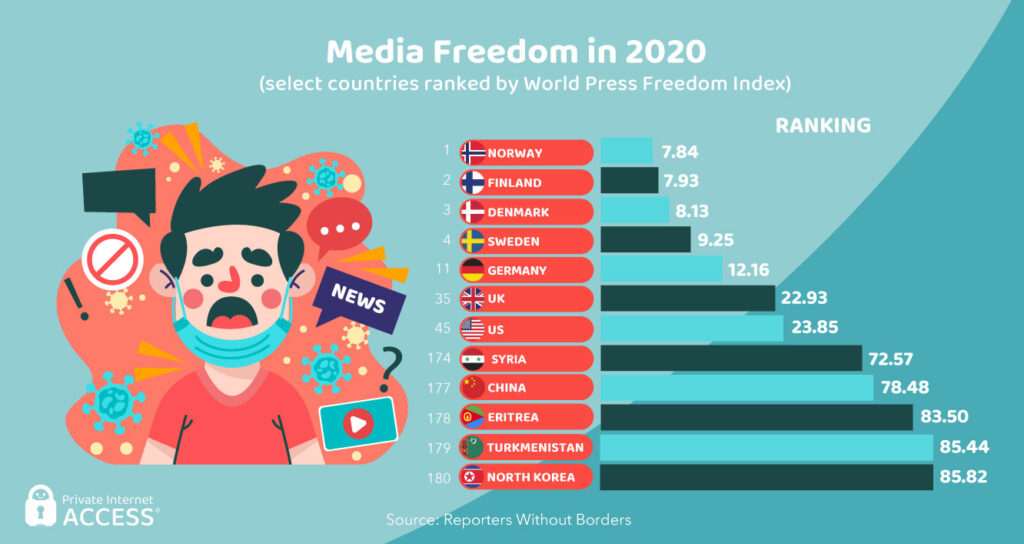

The RSF’s World Press Freedom Index for 2020 has demonstrated a further, profound impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on the freedom of the media as it amplified the crises threatening it.

Specifically, its global indicator has dropped by 12% since the introduction of the metric in 2013, while the percentage of countries with the ‘very bad’ press freedom situation increased by two points, to 13%.

In 2020, Norway was ranked as the best country for media freedom for the fourth consecutive year. It was closely followed by Finland and Denmark. At the end of the list were North Korea (180th place), Turkmenistan (179), Eritrea (178), and China (177).

Syria had slightly improved its media freedoms compared to 2016, but was still ranking very low – 174th in 2020. It was followed by Iran, which went down by three places compared to the previous year and landed in the 173rd position.

Germany improved its media freedom index by 5 points since 2016, ranking 11th in 2020. The UK advanced by three places in 2020, to the 35th position.

The situation in the US declined, placing the country in the 45th position in 2020.

Worst Countries for Media Freedom According to Local Opinion

According to a Gallup World Poll from 2016, the share of people agreeing that the media had a lot of freedom was the highest in Western Europe. The countries that stood out were Denmark, Norway, Finland, Switzerland, the Netherlands, Ireland, and Sweden.

This percentage was the lowest in Mauritania (22%), DR Congo (26%), South Sudan (28%), Gabon (29%), Ukraine (29%), and Venezuela (29%). They were followed by Yemen and Republic of Congo, both at 30%, Belarus at 32%, and Moldova at 35%.

Americans Are More Supportive of All Forms of Expression

Americans are more accepting of different forms of speech than the rest of the world, with 52% believing sexually explicit statements should be allowed, and 44% believing the same about calls for violent protests.

Worldwide, 80% of the public believes people should be allowed to freely criticize government policies.

Only 35% believe they should be allowed to publicly express statements that are offensive to minority groups or religiously offensive. An even smaller number supports calls for violent protests or sexually explicit statements.

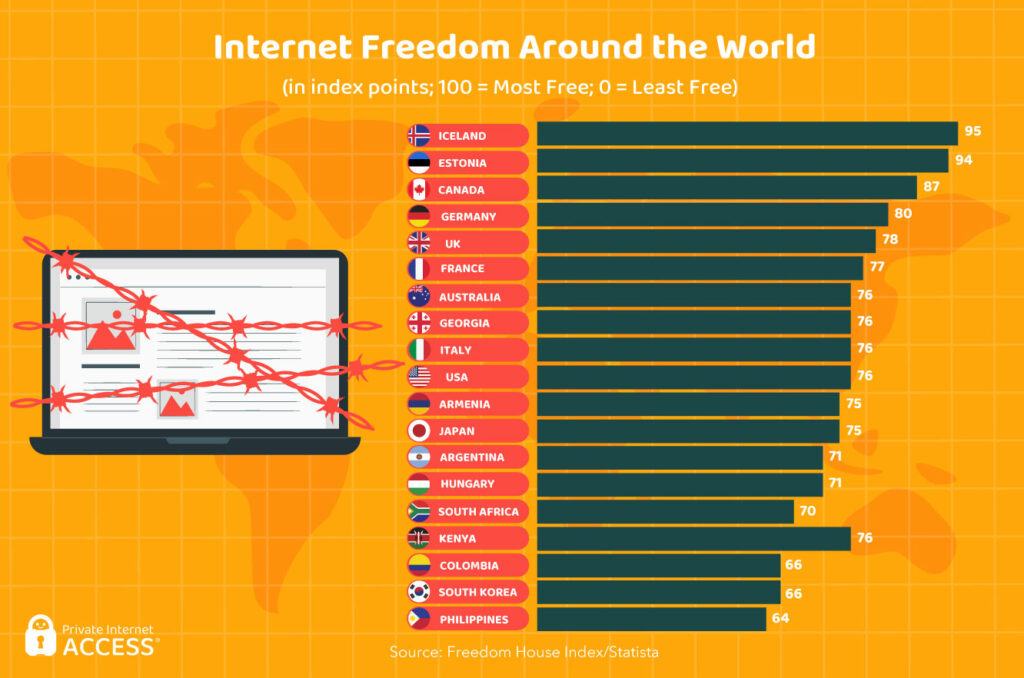

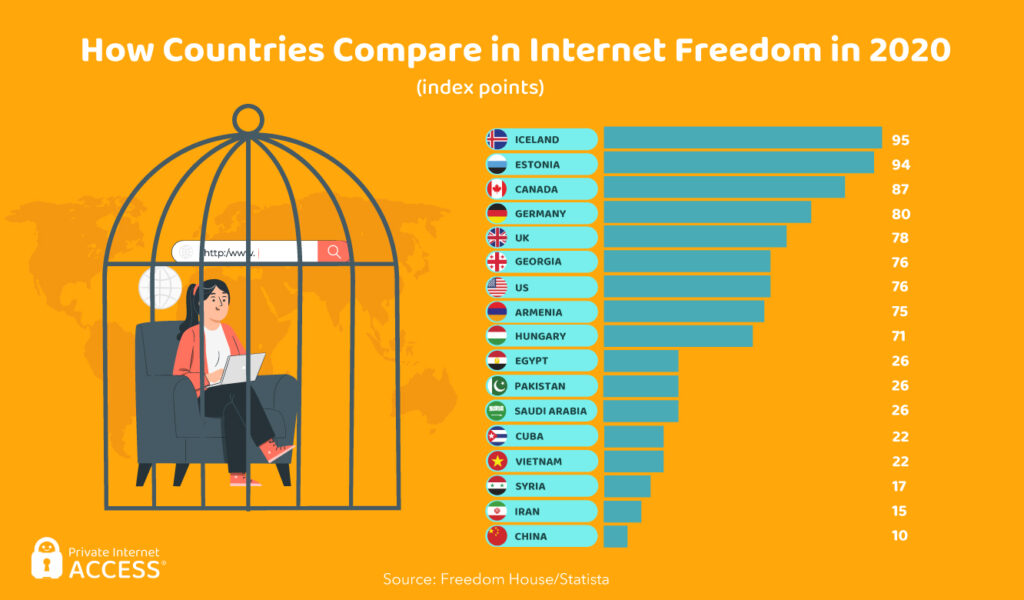

Iceland Has the Highest Level of Internet Freedom

According to the 2020 Freedom House Index, Iceland is the country where people enjoy the highest degree of online freedom, with the highest index (95).

Iceland is followed by Estonia (94 index points), Canada (87), and Germany (80). United Kingdom has 78 points, while France has 77 index points.

Australia, Georgia, Italy, and the United States have the same internet freedom index of 76 points.

Rights to Internet Access

The right to internet access refers to the position that everyone must be able to access and use the internet. This gives them a key means to enjoy their right to freedom of expression and opinion, as well as other fundamental human rights.

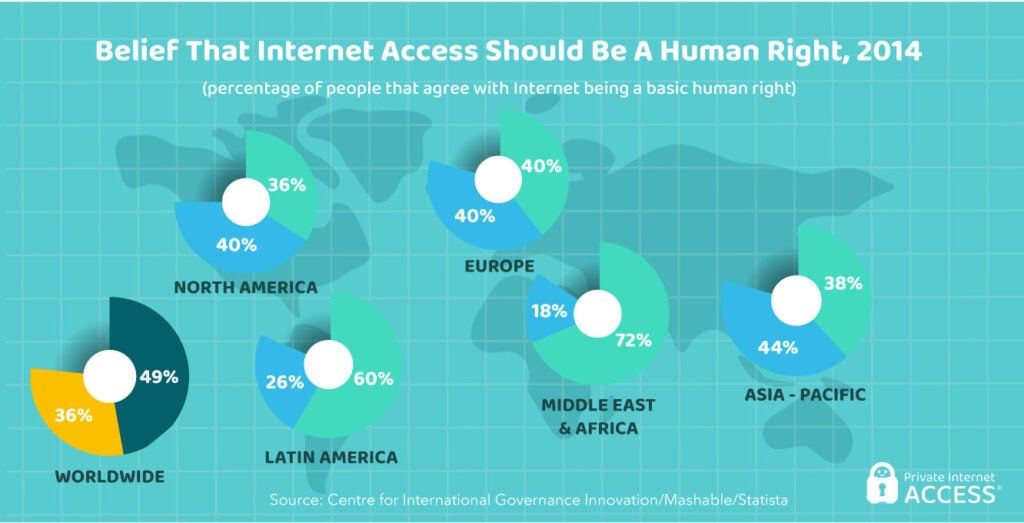

Internet Access As A Human Right Is Not A New Belief

Already for a number of years, people around the world have held the belief that internet access should be a basic human right to at least some degree. As far back as 2014, in an Ipsos poll, 49% of respondents strongly agreed on the matter, while 34% somewhat agreed.

Those who strongly supported considering internet access a human right were the overwhelming majority in traditionally developing regions – Latin America, Middle East, and Africa.

In other regions, where internet access is more of a commodity than a luxury, people have felt less strongly in favor of the internet as a basic human right.

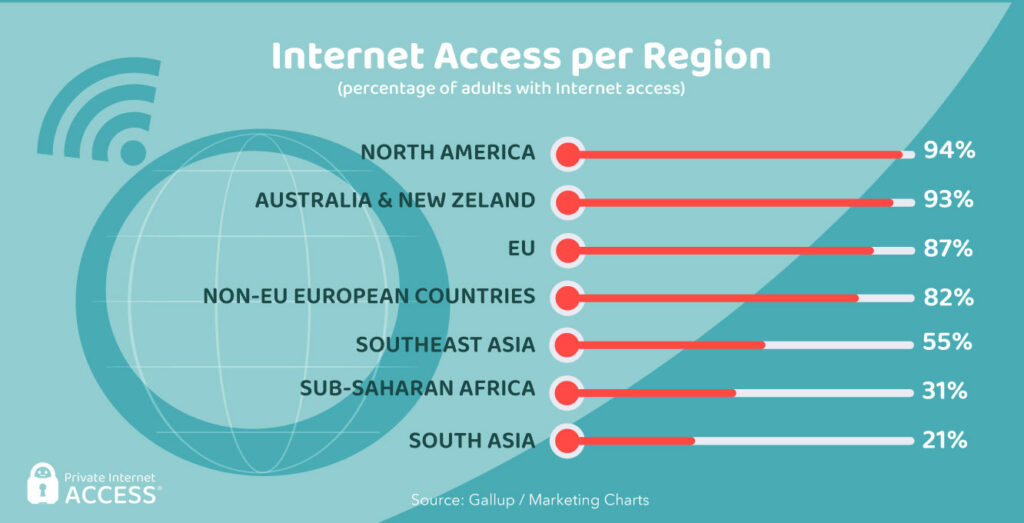

Global Internet Access in Different Regions

Although the share of adults using the internet around the world is increasing, the gap between the regions remains wide.

At the forefront are the regions such as North America (94%), Australia and New Zealand (93%), the EU (87%), and European countries outside the EU (82%).

The poorest performing regions are South Asia (21%), sub-Saharan Africa (31%), and Southeast Asia (55%).

Younger adults in these regions are the ones driving the increase. In Indonesia, a country with a relatively low rate of internet usage, 89% of 18-29-year-olds use the internet, compared to 58% of 30-49-year-olds and 24% of adults 50+.

In the US, almost every adult person aged 18-49 uses the internet, compared to 84% of those 50+.

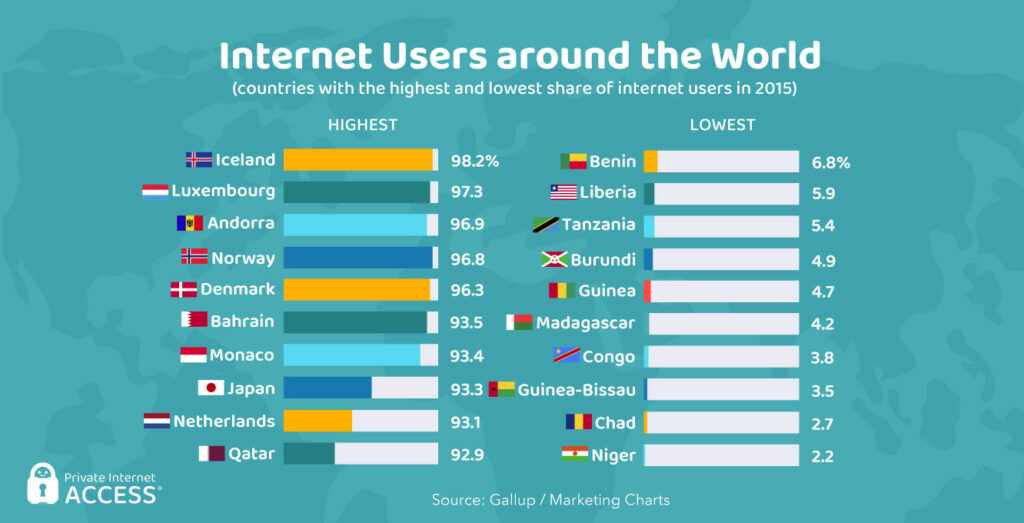

Countries with Highest and Lowest Percentage of Individuals Using Internet

In 2015, Iceland, Luxembourg, Andorra, Norway, Denmark, Bahrain, Monaco, Japan, the Netherlands, and Qatar had the highest share of individuals using the internet (all above 90%), according to the research of the UN International Telecommunications Union.

On the other end of the scale were Niger, Chad, Guinea-Bissau, Congo, Madagascar, Guinea, Burundi, Tanzania, Liberia, and Benin. These countries had less than 7% of internet users at that time.

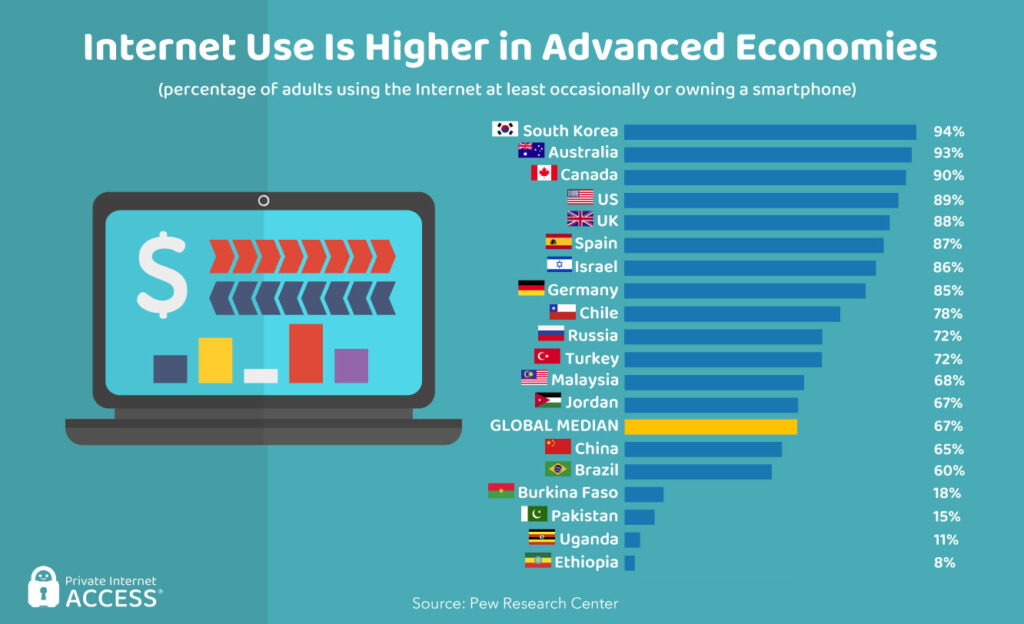

Advanced Economies Have Higher Internet Use

In 2015, Pew Research Center analyzed 40 different countries. It discovered that 67% of respondents across these countries either used the internet occasionally or possessed a smartphone (classifying them as internet users).

The predominant countries in this matter are South Korea (94%), Australia (93%), and Canada (90%). High rates (over 80%) had also been found in the US, UK, Spain, Israel, and Germany.

The rates of internet access were the lowest in Ethiopia (8%), Uganda (11%), Pakistan (15%), and Burkina Faso (18%), demonstrating a strong correlation between a country’s wealth and internet access.

Despite lower rates in emerging economies, internet use in those countries was increasing. Especially noticeable are Turkey, Jordan, Malaysia, Chile, Brazil, and China, all of which had recorded double-digit increases in the internet use percentage.

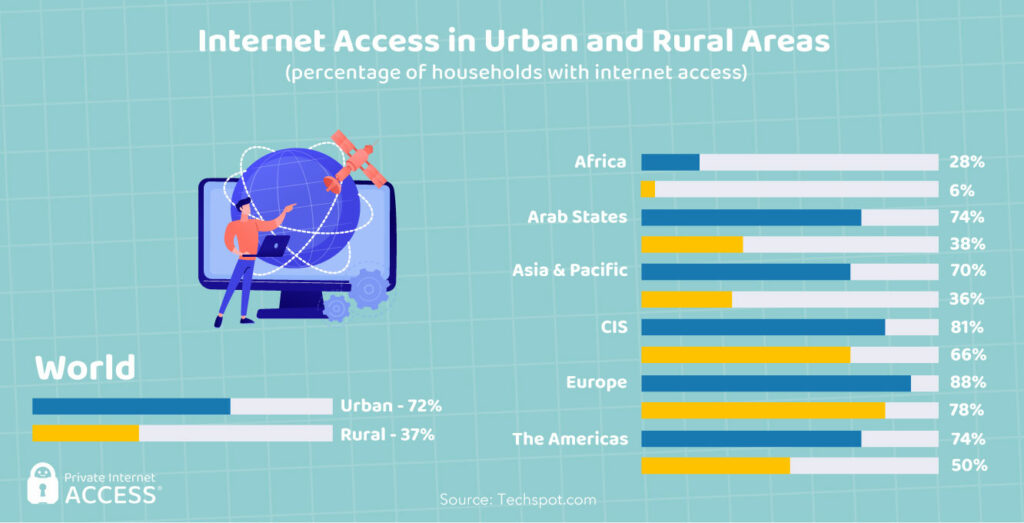

Rural Areas Around the World Lag Behind in Internet Access

About 72% of households in urban zones worldwide had access to the internet in 2019. By comparison, this share was only 37% for rural locations.

As a rule, the gap between urban and rural areas was narrower in developed countries. In the developing countries, 2.3 times more households in urban areas had internet access than in rural locations.

The disparities were most obvious in Africa. Here, only 28% of urban households had an internet connection, but even that was 4.5 times higher than in rural zones (6.3%).

As for most other areas, household internet access in urban zones ranged between 70-88%. In rural locations, this share was between 37-78%.

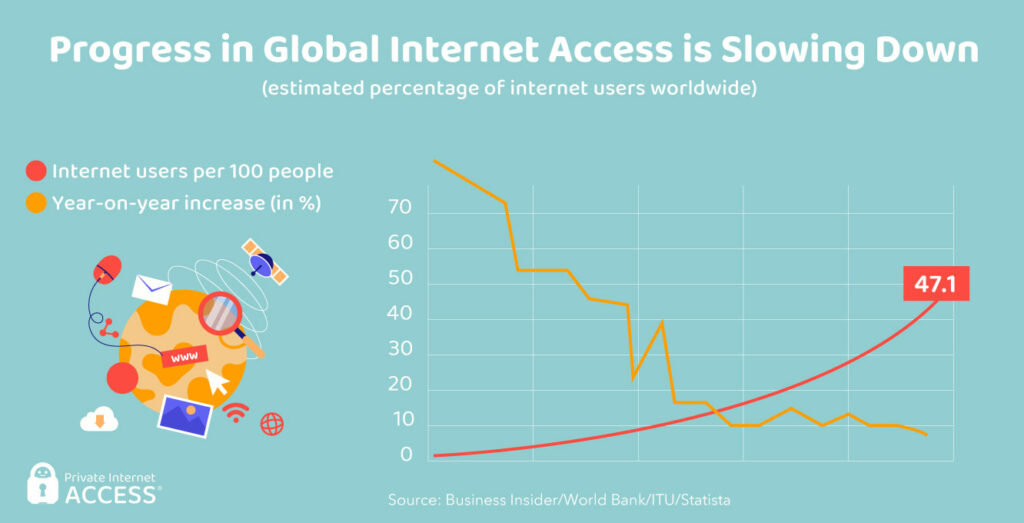

Global Internet Access Rising More Slowly

According to Business Insider, only 47.1% of the world’s population had internet access in 2016. This meant that close to 4 billion people, mostly in developing or less-developed countries, didn’t.

The year-on-year growth was the highest in the 1990s. The growth largely diminished since then and between 2013 and 2016 it dropped below 10% and stayed there. That said, a more recent survey from Gallup indicates that the last few years have seen a boost again.

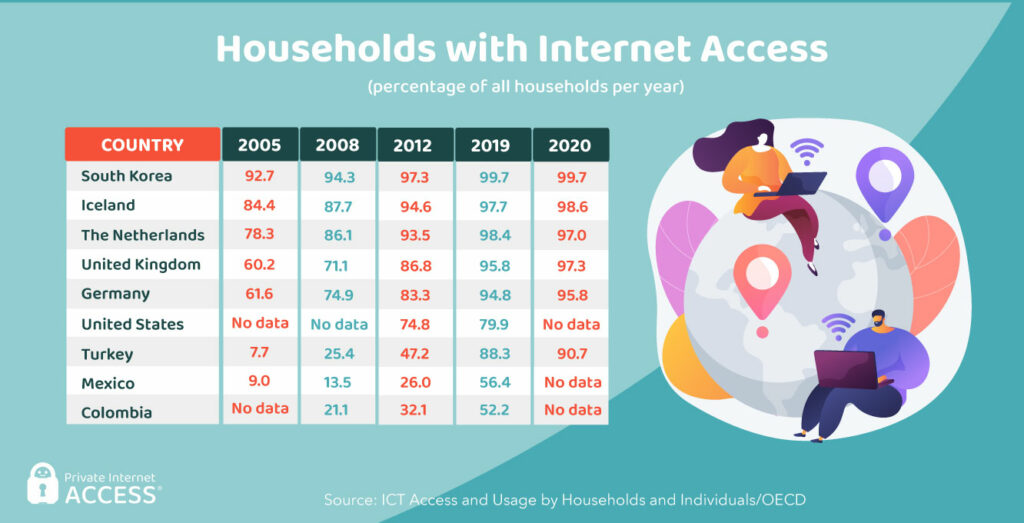

Households with Internet Access over the Years

In 2005, South Korea and Iceland led in the share of households with internet access. The former had 92.7% and the latter somewhat lower in coverage – 84.4% of households.

The Netherlands was in third place, with 78.3% of households having access to the internet.

At the very end of the list were Turkey and Mexico with less than 10%.

In the period between 2005-2020, the situation improved in all the analyzed countries. The three top countries kept their leading positions.

Turkey had the most dramatic increase, from 7.7% in 2005 to 90.7% in 2020.

In 2019, Colombia was the least connected country, with only 52.2% of households having the internet.

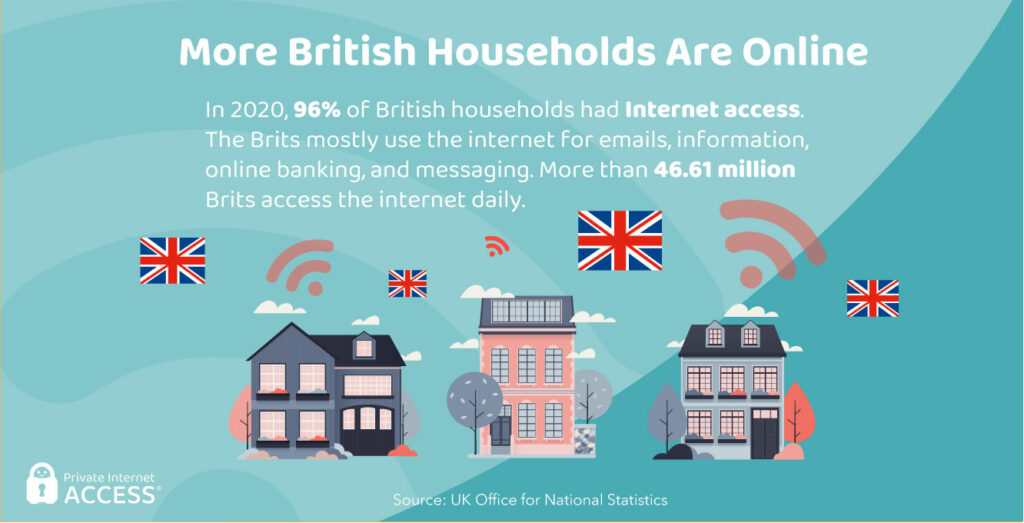

British Households with Internet Access

In 2020, 96% of British households had internet access, up from 83% in 2013. In 2013, there were 4 million British households without internet access. This number dropped to 1.5 million in 2020.

In 2013-2020, sending and receiving emails and finding information on goods and services remained the two top internet activities for British adults. However, reading or downloading online news, which in 2013 was in the third position, was replaced in 2020 by internet banking.

For comparison, internet banking was in sixth place in 2013. Messaging apps, which appeared in the meantime, took over the fourth position in 2020, replacing social networking (e.g. Facebook, Twitter, etc.) which was in that position in 2013.

In 2013, 36 million (73%) British adults accessed the internet daily, compared to 46.616 million in 2020. More than half of them (53%) used a mobile phone to access the internet. By comparison, 84% of British adults owned a smartphone in 2020.

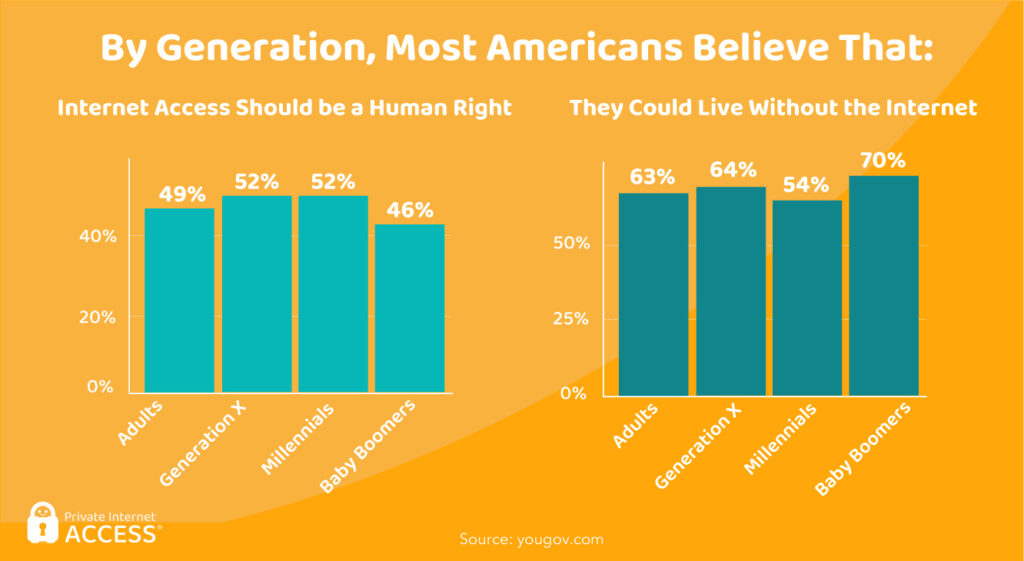

What Different Generations of Americans Think About the Internet

In 2019, 49% of adult Americans believed internet access should be a human right. Millennials and Gen-Xers made up 52% of this group, while Baby Boomers weren’t as convinced and made up 46% of the total number of supporters.

The majority of Americans said they could live without the internet (63%), but 37% believed it had become a slight necessity. Expectedly, the share of Baby Boomers among those who could live without it was the highest – 70%, while 64% of Gen-Xers and 54% of Millennials share this view.

More than half of the respondents (53%) said they were looking forward to the 5G network, while only 29% said this wouldn’t be very helpful or even at all.

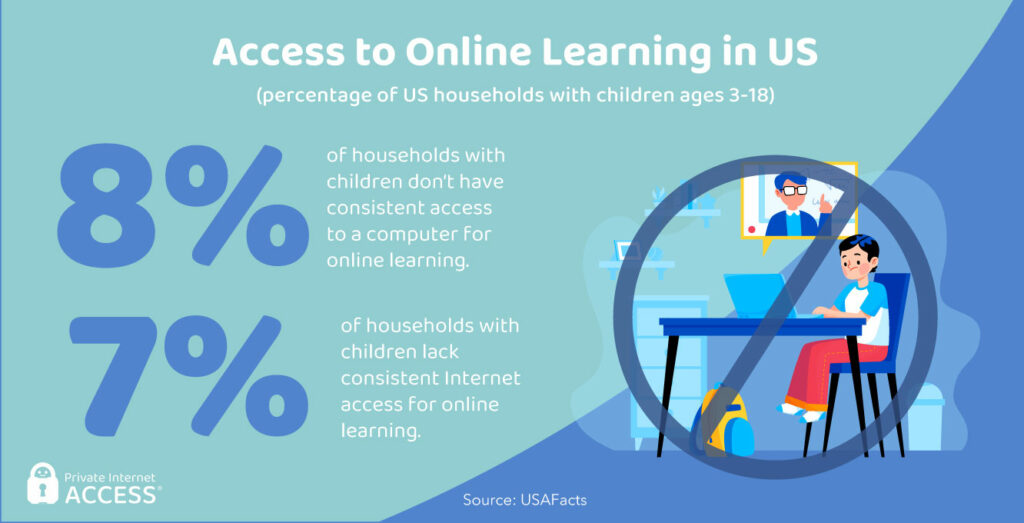

Access to Online Learning in US

In 2020, the US Census Bureau found that 8% of households (around 4.4 million) with children aged 3 to 18, did not have consistent access to a computer for online learning.

Of the 52 million households with children interviewed, 74% had constant access to a computer for online learning and 16% had it most of the time.

Among the households who had consistent access to a computer, 60% were given these devices by the child’s school or school district.

Despite many households receiving these devices, the research found that 7% of households with children (3.7 million) still lacked consistent internet access for online learning.

Among households that always had internet access, 2.4% had received it from the child’s school or school district.

Freedom from Internet Censorship

Internet censorship is the practice of control or suppression of what individuals or organizations can access, publish, or view on the internet. It may be enacted by governments or private organizations by the instruction of regulators, governments, or on their own initiative.

Internet Freedom Comparison, by Country

Internet censorship is the lowest in Iceland, which scored the highest on the 2020 Freedom House Index in the degree of internet freedom. With 95 points out of 100, Iceland is followed by Estonia (94), Canada (87), Germany (80), and the UK (78).

Interestingly, Georgia (76), Armenia (75), and Hungary (71) scored among the first 15 countries. The US had the same number of points as Georgia and Kenya (76).

At the very end of the list are China with only 10 points, Iran (15), Syria (17), as well as Vietnam and Cuba (both 22).

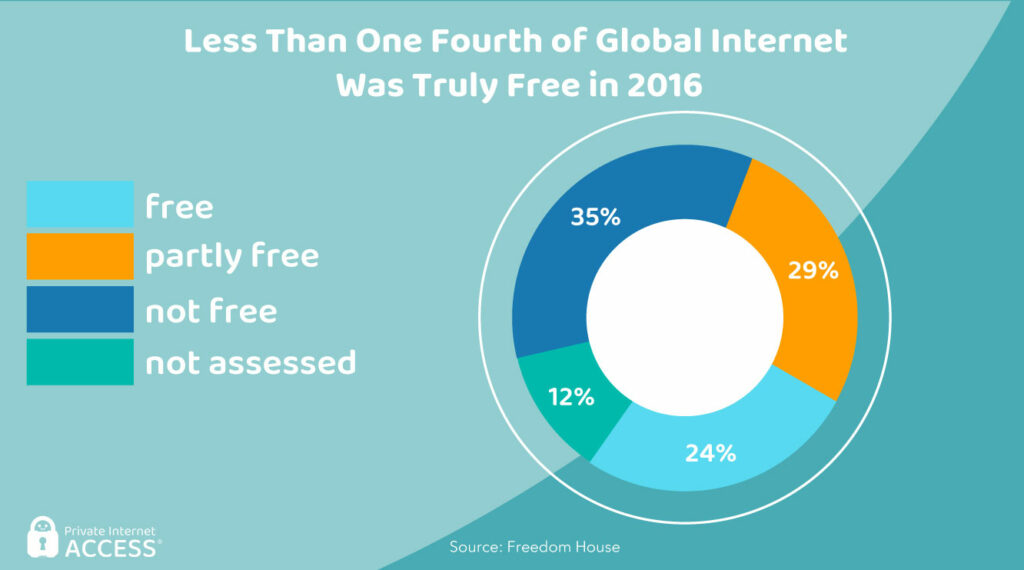

Only 24% of Global Internet Users Can Freely Express Themselves Online

According to Freedom House’s 2016 study, only 24% of the global internet population is considered free – meaning popular messaging and social media platforms can be freely used for online communication and expression. The partially free internet population is 29%, while 35% is considered “not free”.

Two-thirds (67%) of internet users resided in countries where criticism of the government, military, or ruling family was subject to online censorship.

In 2015, 38% of internet users lived in countries that blocked social media or messaging apps.

According to the Committee to Protect Journalists, the ten most censored countries in the world are Eritrea, North Korea, Turkmenistan, Saudi Arabia, China, Vietnam, Iran, Equatorial Guinea, Belarus, Cuba.

Voicing Opinion Can Land You in Jail in Some Countries

In 2015, 58% of internet users resided in countries where blogging about political, social, or religious issues has been known to put people in jail.

As much as 45% of internet users resided in countries where censorship and jail time are used against those posting satirical texts, videos, or cartoons online.

Thirty eight percent of internet users lived in countries that block social media or messaging apps.

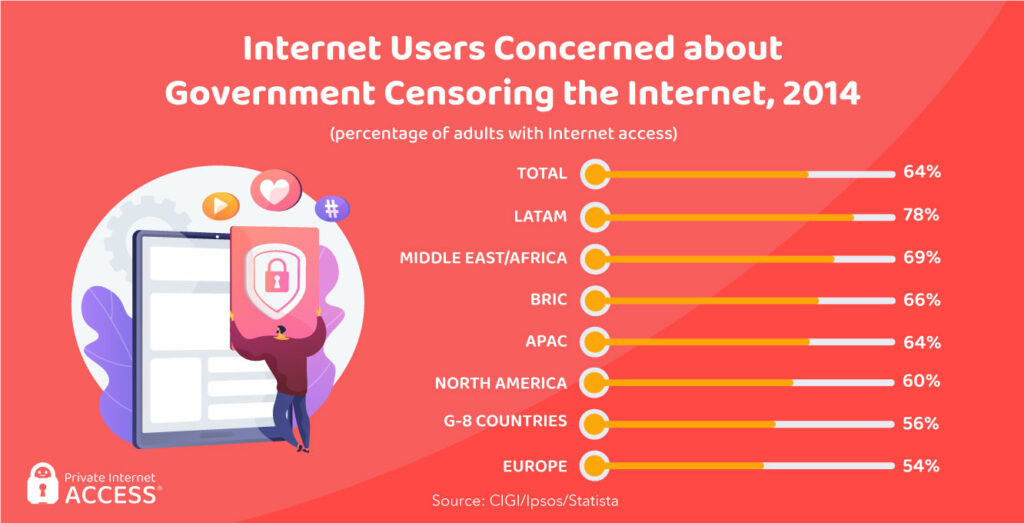

Internet Censorship and Public Concern

A study by CIGI and Ipsos in 2014 revealed that 64% of people worldwide were concerned about the government censoring the internet. The respondents from Latin America were the most concerned (78%), followed by Middle East/Africa (69%). In Europe, 54% of people expressed concern.

This contrasts with a 2010 global poll by the BBC, which found that state censorship of content wasn’t even among the three most common internet-related concerns in 26 countries around the world. Only 6% of them were worried about censorship.

After the Arab Spring of 2011, internet censorship had increased in Tunisia, Libya, and Egypt, where it had reached pervasive levels.

Blocked Websites, from Politics to Sex

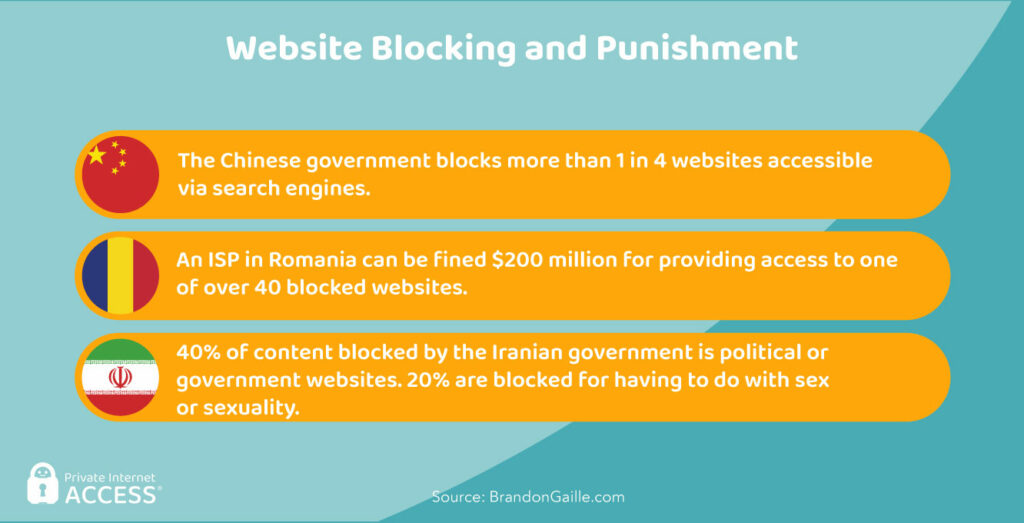

In China, more than one in four websites typically accessible via Google or other search engines are blocked by the government. In 2017, the number of affected websites was nearly 1,000.

China uses various methods to censor the Internet, including IP blocking, DNS filtering and redirection, URL filtering, packet filtering, and connection reset – all commonly known as the Great Firewall of China.

In Romania, an ISP faces a fine of $200 million if it is found to provide access to one of more than 40 blocked websites.

In Iran, 40% of the content blocked by the government is political or government websites. Another 20% is blocked due to being related to sex or exploring sexuality.

Silencing Social Media and Communication Apps

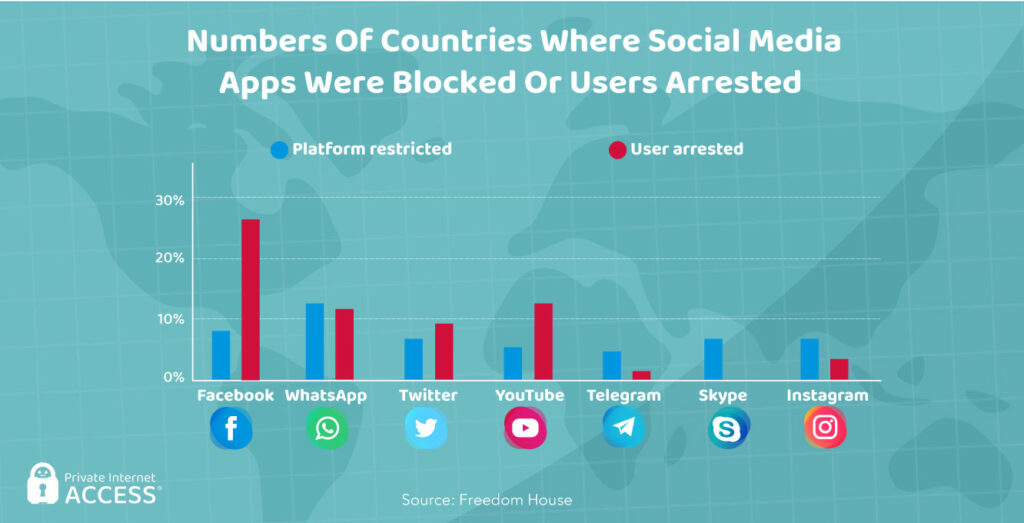

The most blocked social media/communications platform in 2016 was WhatsApp, blocked in 12 countries. Users of Facebook were under the most pressure, arrested for posting political, social, or religious content in 27 countries.

The total number of countries restricting popular social media platforms was 24 in 2016, while the number of countries arresting users because of the content on them was 38.

The number of countries arresting people over posting or even liking offending material on social media had increased by more than 50% between 2013 and 2016.

Rise of VPNs in Response to Censorship

One of the methods that internet users have been resorting to help them bypass censorship and provide them with access to the content blocked in their area is a Virtual Private Network (VPN).

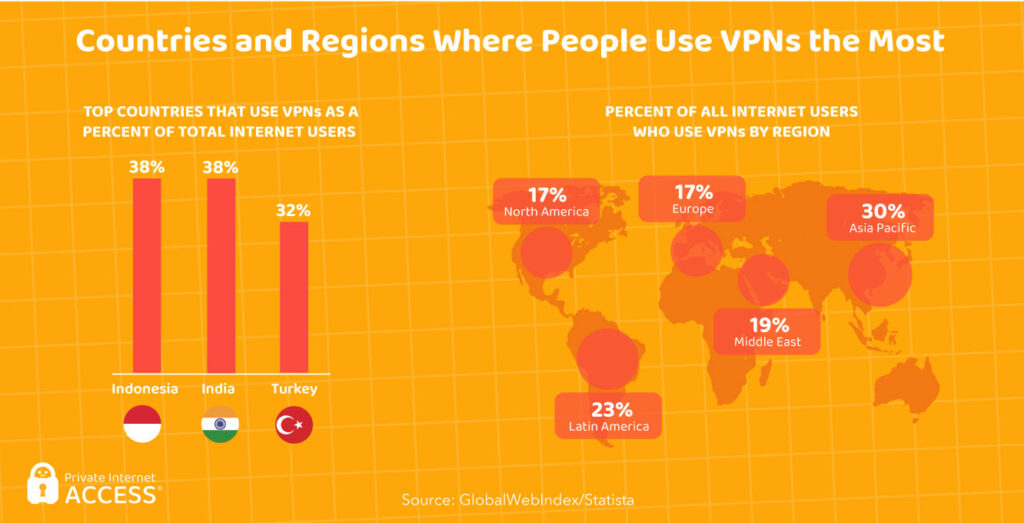

Top countries by share of VPN users among total internet users are Indonesia (38%), India (38%), and Turkey (32%). Asia-Pacific is the region with the highest number of VPN users (30%), followed by Latin America (23%), and the Middle East (19%).

The main reason for using a VPN is access to better entertainment content, followed by access to social networks or news services. Namely, 35% of mobile device users and 34% of computer users state it as the reason for using a VPN. Other leading motivations include browsing anonymity, access to sites and services at work, and communication with friends and family abroad.

From Selective to Total Censorship

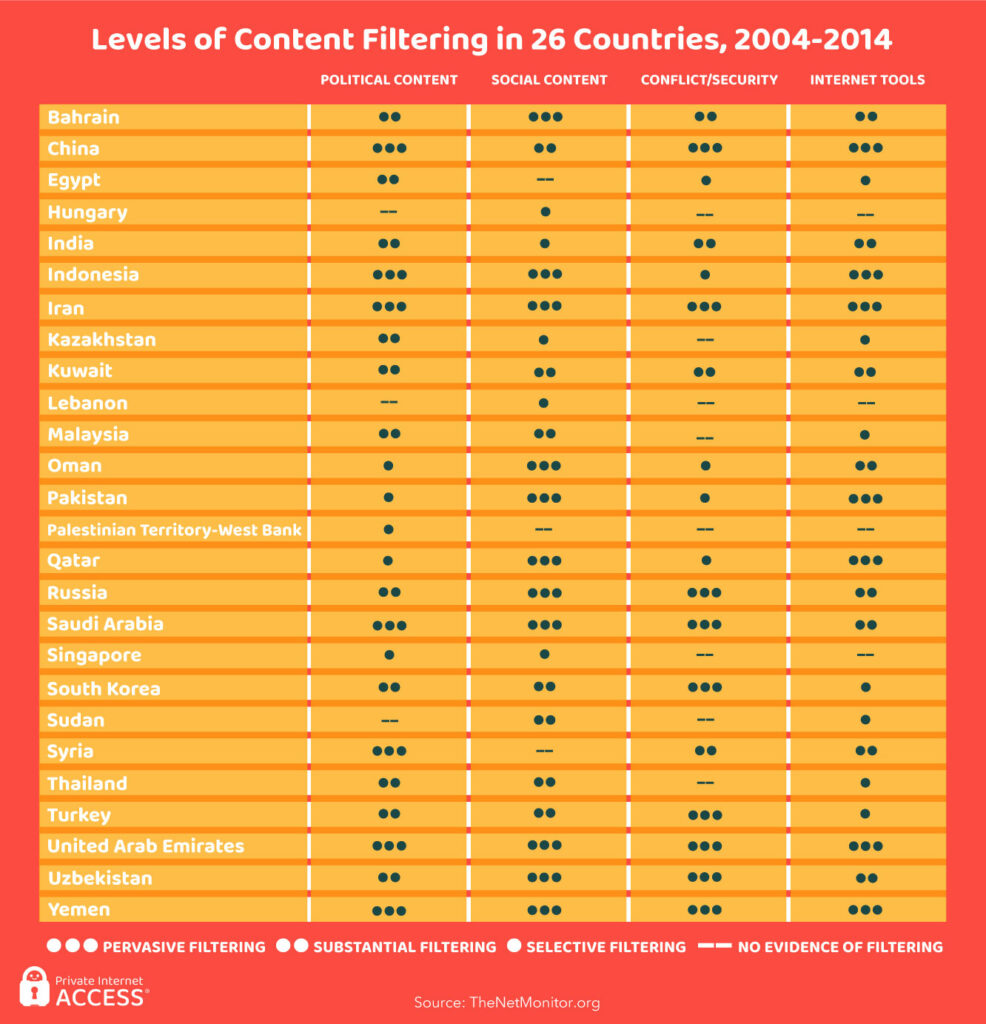

Between 2004 to 2014, 26 out of 45 countries filtered internet content on their respective territories.

Bahrain pervasively filtered social content (i.e. content that goes against a country’s societal norms, including pornography, LGBTQ+ content, online dating, gambling, alcohol and drugs, etc.).

China pervasively blocked political content (content related to news and media, religion, human rights, environmental controversy, and freedom of expression), conflict and security content (content perceived or stated as a threat to national security), and internet tools (e.g. anonymizers, censorship circumvention tools, streaming and P2P file sharing sites, social media platforms).

Indonesia mostly focused on political content, social content, and internet tools. Yemen, Iran, and United Arab Emirates pervasively filtered all four categories – political content, social content, conflict/security, and internet tools.

In Hungary and Lebanon, there was only selective filtering of social content, while Singapore selectively filtered social and political content.

Internet Shutdowns as a Censorship Tactic

Beyond selective filtering of the internet, some countries also resort to full internet shutdowns, with India recording 20 incidents in the first six months of 2017. Bahrain, Ethiopia, Pakistan, Iraq, Turkey, and Malaysia carried out country-wide or partial internet shutdowns in 2016.

These shutdowns, which can drag on for hours or even days, are mostly implemented in response to social and political events. For instance, the Indian government has used them to “prevent violence fueled by rumors circulated on social media or mobile messaging applications.”

Internet shutdowns as a censorship tactic were pioneered by Nepal in February 2005, when all internet connections in its territory were severed upon declaring martial law.

Emerging Economies Favor Freedom on the Internet

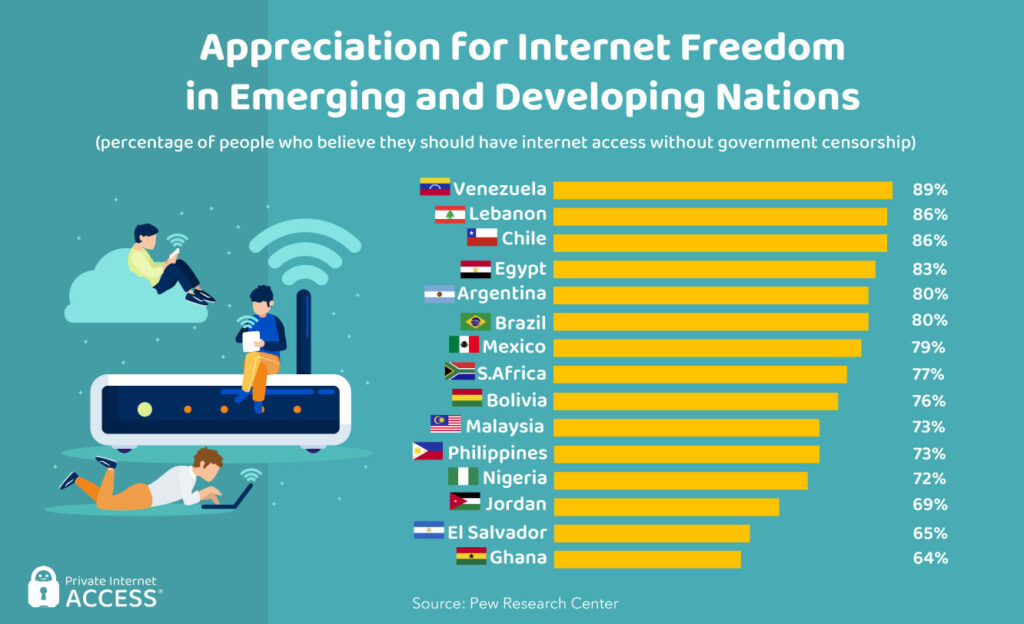

In 2013, the majority of people in developing and emerging countries (22 out of 24) said it was important to have internet access free of government censorship.

The opposition to censorship was most pervasive in Venezuela (89%), Lebanon (86%), Chile (86%), Egypt (83%), Argentina (80%), and Brazil (80%). It was only Pakistan (22%) and Uganda (49%) where less than half of the respondents disagreed.

The overwhelming support for internet freedom also tends to coincide with high internet usage. The most obvious examples are Chile and Argentina, where two-thirds of the population already had internet access.

Net Neutrality

Net(work) neutrality is the idea that internet service providers (ISPs) must treat equally all content transmitted through their infrastructure. In other words, they shouldn’t discriminate based on website, content, user, source address, platform, application, equipment type, or communication mode.

Net Neutrality Around the World

Although the principle of net neutrality has largely been a heated issue in the US, it is also becoming a concern on the global level, which is why some countries have already enacted laws to protect it.

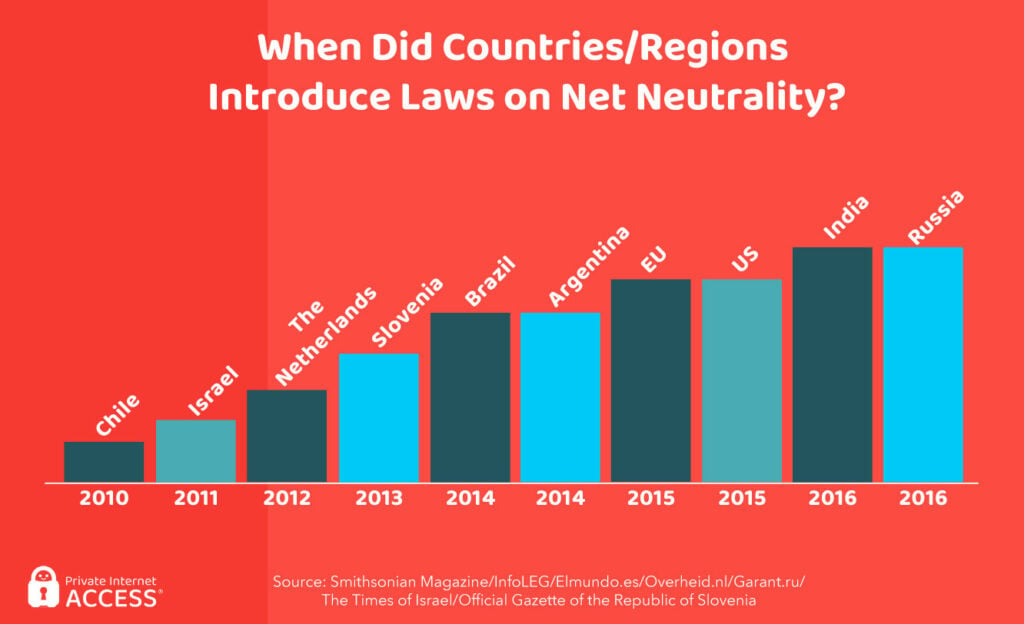

The first country to adopt net neutrality legislation was Chile. In 2010, this country enacted a law prohibiting companies like Facebook or Wikipedia from subsidizing mobile data usage for consumers. Exceptions exist for ensuring security and privacy.

In 2014, Brazil enacted its Civil Rights Framework for the Internet, which only allows internet service companies to prioritize certain types of traffic for technical reasons (e.g. overloaded networking capacity).

Argentina also introduced Articles 56 and 57 of its Law 27,078 in 2014, protecting users’ rights to access any content without restriction and introducing prohibitions for companies to interfere with these rights under the principle of net neutrality.

The European Union first introduced similar regulations in 2015. They require internet access providers to treat all traffic equally, only allowing flexibility to restrict traffic in situations when network equipment is operating at maximum capacity, to protect network security, and in emergencies.

In the United States, rules on net neutrality went into effect in June 2015, after the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) published the final rule on its new net neutrality regulations in April.

In 2016, the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India enacted rules prohibiting service providers from offering or charging discriminatory tariffs for data services based on content. In 2017, the body also introduced rules protecting against content and application discrimination.

Net Neutrality According to European Consumer Opinion

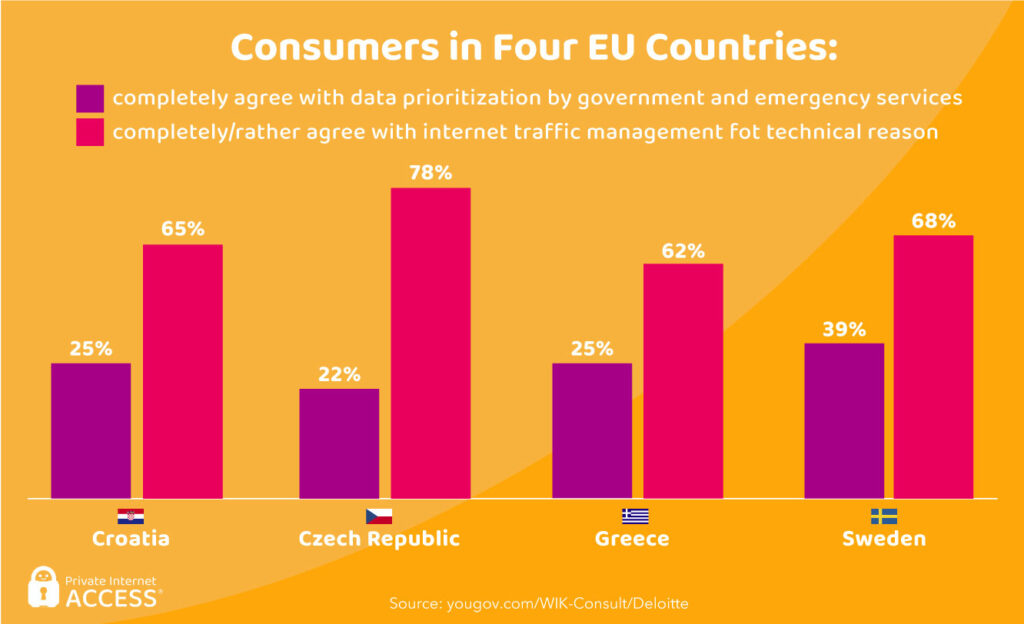

A 2015 study of consumer opinion in four EU countries – Croatia, Czech Republic, Greece, and Sweden, delivered some interesting results.

When asked about the prioritization of certain important data on the internet, such as that of the government and emergency services, only 25% of consumers in Greece and Croatia said they “completely agree” with it. The public opinion on this matter was significantly higher in Sweden (39%) but slightly lower in the Czech Republic (22%).

On the other hand, consumers in all four countries expressed overwhelming support for traffic management measures that keep their internet experience stable. This was especially noticeable in the Czech Republic, where the share of those who “completely” or “rather agree” with such measures was 78%.

Net Neutrality and American Support

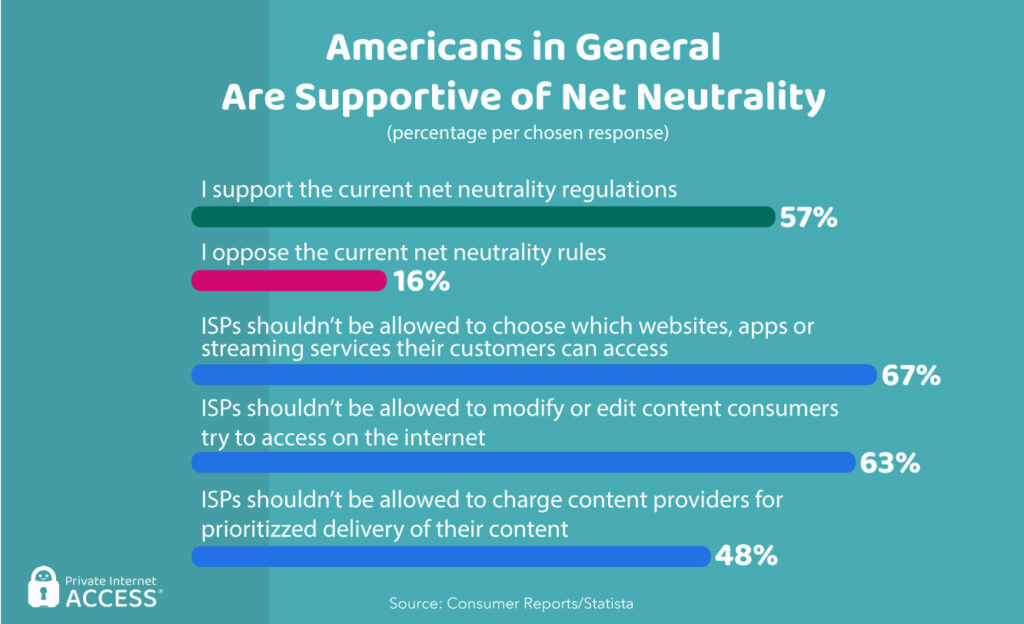

In 2017, 57% of Americans supported the net neutrality regulations, while 16% of them voiced their disagreement.

Sixty-seven percent of interviewees said ISPs shouldn’t be allowed to decide which websites, streaming services, or apps their customers can access. Sixty-three percent of them believed ISPs shouldn’t be able to edit or modify online content their consumers are trying to access.

The respondents were more indecisive about whether ISPs shouldn’t be allowed to charge content providers for prioritized delivery of their content. Less than half of them said that they shouldn’t.

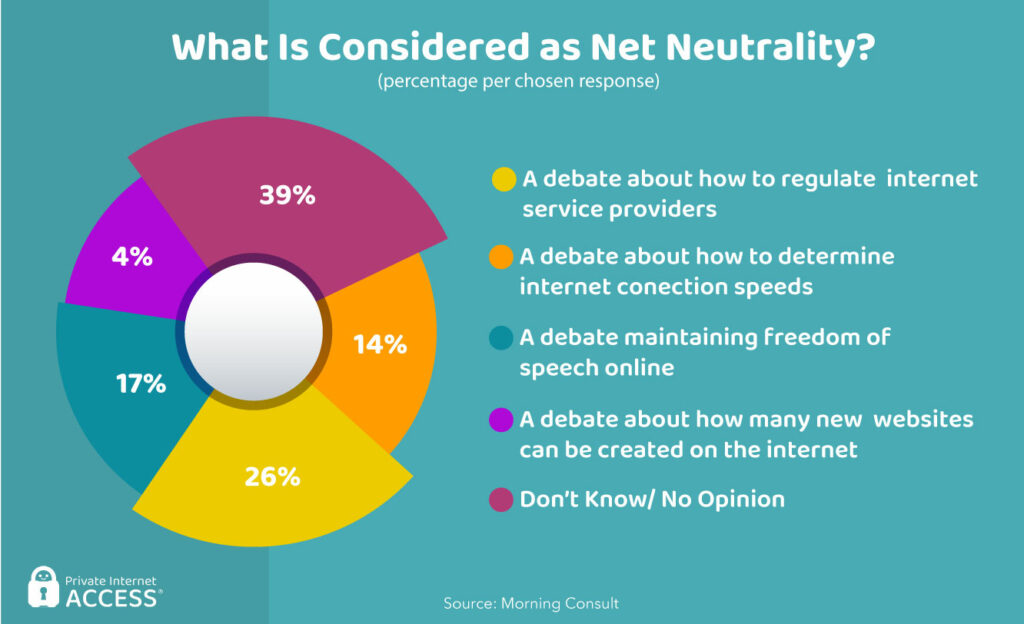

How Americans First Understood Net Neutrality

Many Americans didn’t understand net neutrality when the debate first surfaced. A 2014 poll showed that 39% of respondents were unsure of what it meant or even had an opinion about it.

Among the offered answers on the definition of net neutrality, 26% said it was a debate about how to regulate internet service providers. Seventeen percent of respondents answered it was a debate about maintaining freedom of speech online.

Fourteen percent considered it a debate about how to determine internet connection speeds. A small percentage (4%) even said it was related to how many new websites can be created on the internet.

Between 2014 and 2017, the Americans’ understanding of net neutrality changed dramatically, and is reflected in the generally supportive attitude in later polls.

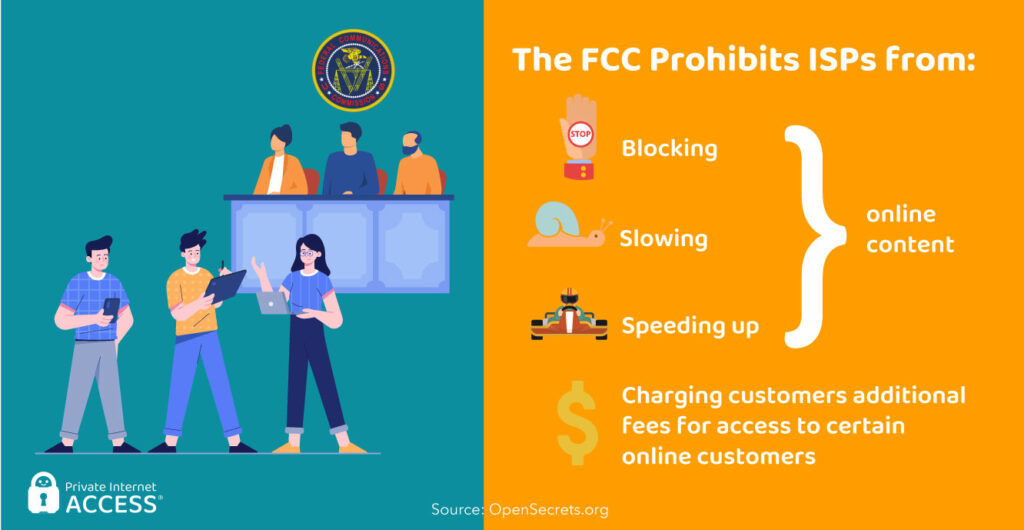

New Rules on Net Neutrality in the US

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC)’s new rules protecting net neutrality, approved in 2015, prohibit ISPs from blocking, slowing, or speeding up online content or charging customers additional fees for access to certain online services.

Under the new rules, ISPs are prohibited from unjust or unreasonable discrimination in services, practices, fees, classifications, regulations, or facilities.

The rules also authorize the FCC to investigate consumer complaints on these matters, while requiring privacy and fair use assurances from ISPs.

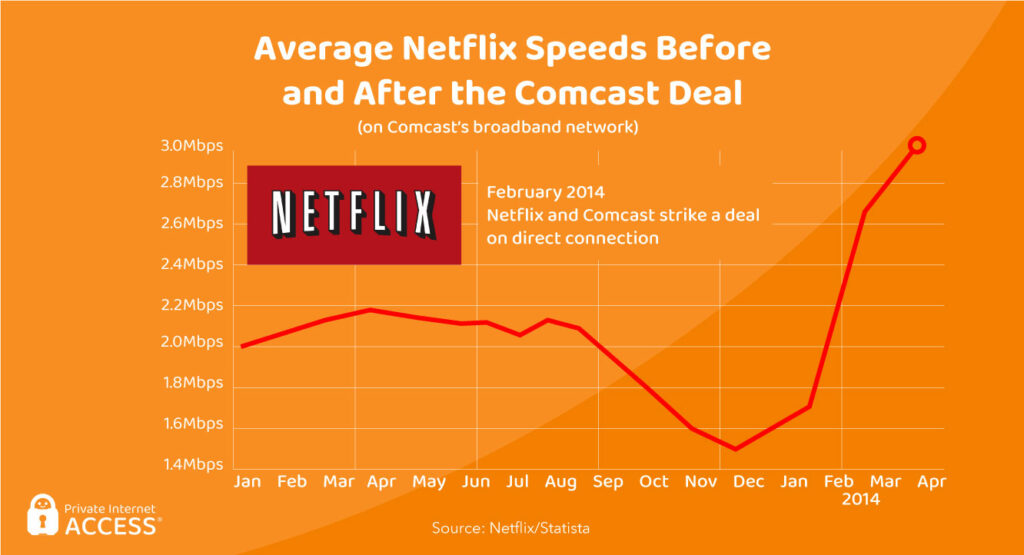

Netflix and Comcast Deal Threatens Net Neutrality

In February 2014, Netflix and Comcast struck a direct connection deal, granting Netflix users on Comcast’s broadband network more than 80% higher connection speeds.

Netflix connection speeds averaged between 2Mbps and 2.1Mbps, reaching their ultimate lows of around 1.5Mbps just before the deal.

After the deal, the speeds improved dramatically, measuring 2.8Mbps in April 2014.

This deal was struck just before the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) approved new rules, in 2015, on net neutrality that demand all content to be treated equally. The rules would prevent ISPs from making similar deals with content providers to grant them privileged access to the ISP’s network, which is against the principle of net neutrality.

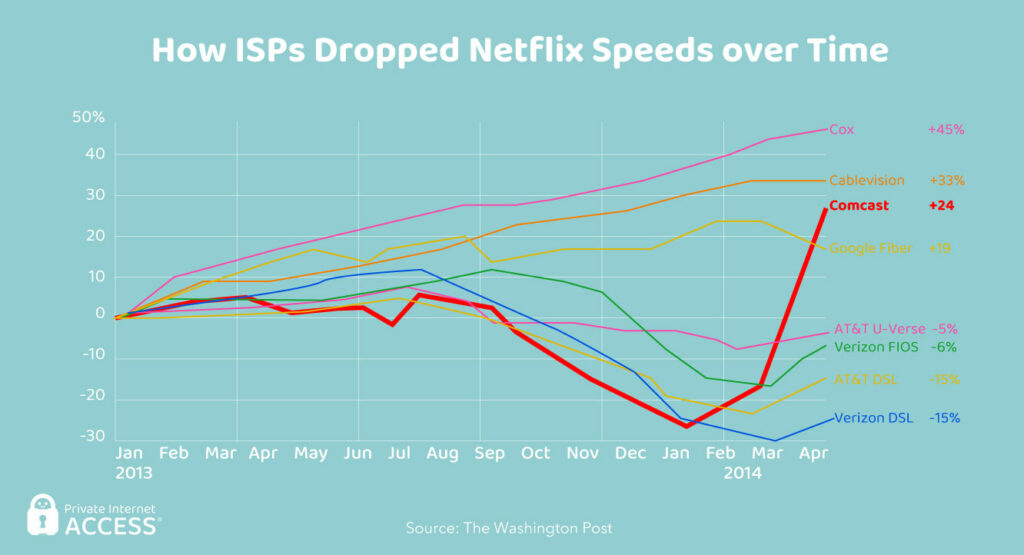

Speed Drops from ISPs Prove Why Net Neutrality Is A Must

Around August 2013, some American ISPs started intentionally slowing down download speeds on Netflix, leading to the accusations of holding Netflix speeds hostage for a higher payment.

Netflix agreed to strike a deal with Comcast in 2014, after which its download speeds improved dramatically with this particular ISP. Poor download speeds were kept by ISPs with whom Netflix hasn’t made a deal.

With such unfair practices, Comcast, AT&T, and Verizon were clearly discriminating against Netflix and its users, demonstrating the necessity of having net neutrality rules in place.

American ISPs Lobbied to Influence Net Neutrality

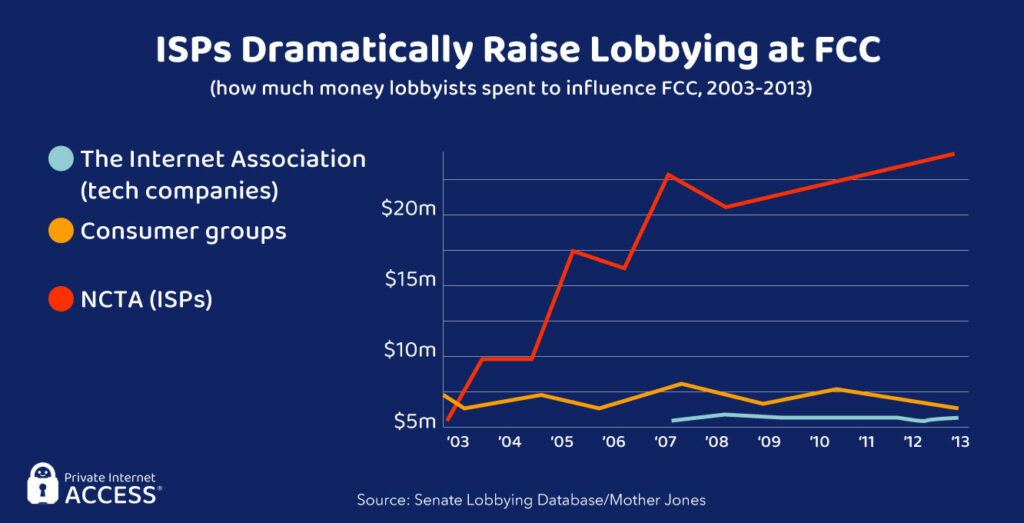

In the first quarter of 2014, ISPs were the largest lobbyists on the issue of net neutrality in the US, having invested $19 million into it. Tech firms invested $7 million (26%), while various consumer groups and content makers participated with $2 million (6%).

Between 2003 and 2013, the money spent by ISPs trying to influence the FCC’s position on the matter steadily increased. The other lobbyists kept it roughly at the same level throughout the years.

Which American ISPs Lobbied the Most?

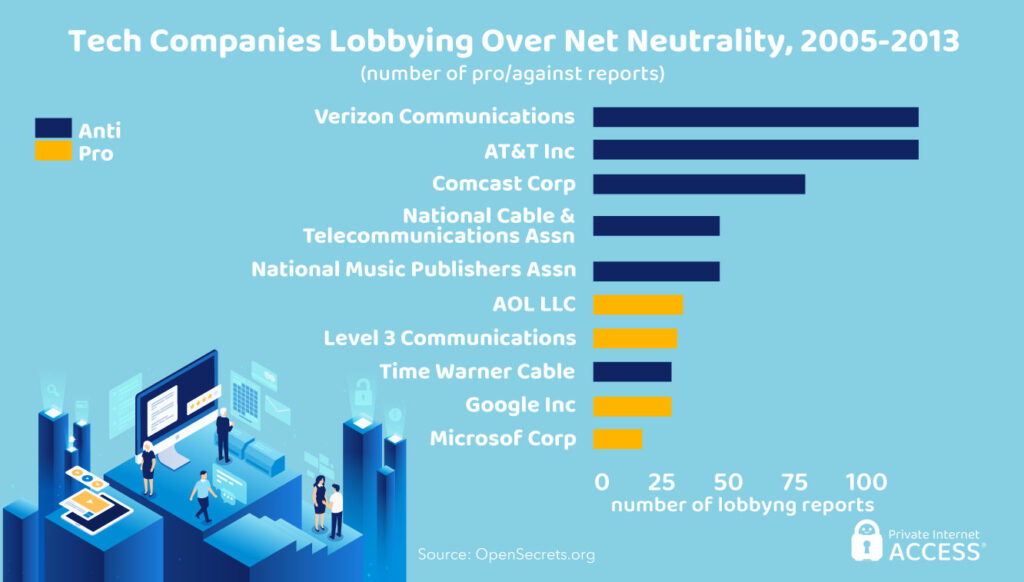

Between 2005 and 2013, the leading companies who lobbied against net neutrality included Verizon, AT&T, Comcast, and National Cable and Telecommunications Association. Those who lobbied in its favor included AOL, Level 3 Communications, Google, and Microsoft.

America’s Biggest Fears About Net Neutrality

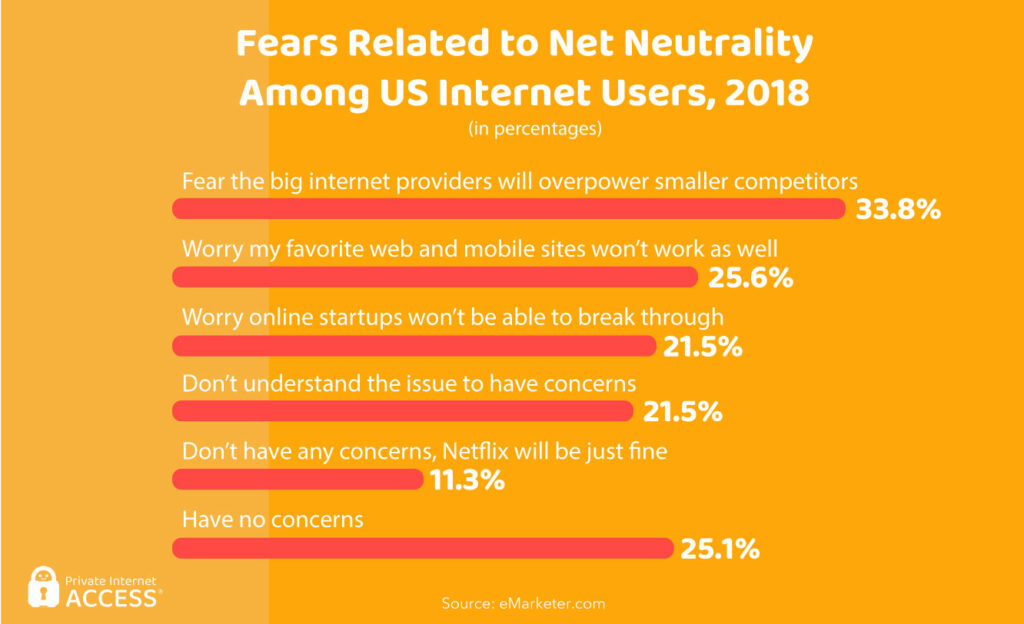

In 2018, 33.8% of adult US internet users expressed fears that net neutrality would allow the big internet providers to overpower their smaller competitors.

More than 25% said they worried their favorite web and mobile sites wouldn’t work as well, while around 21% were concerned about online startups not being able to break through.

Only 11.3% said they didn’t have any concerns and that Netflix would be just fine. That said, more than 21% of respondents said they didn’t understand the issue enough.

The Positive Economic Impact of Net Neutrality

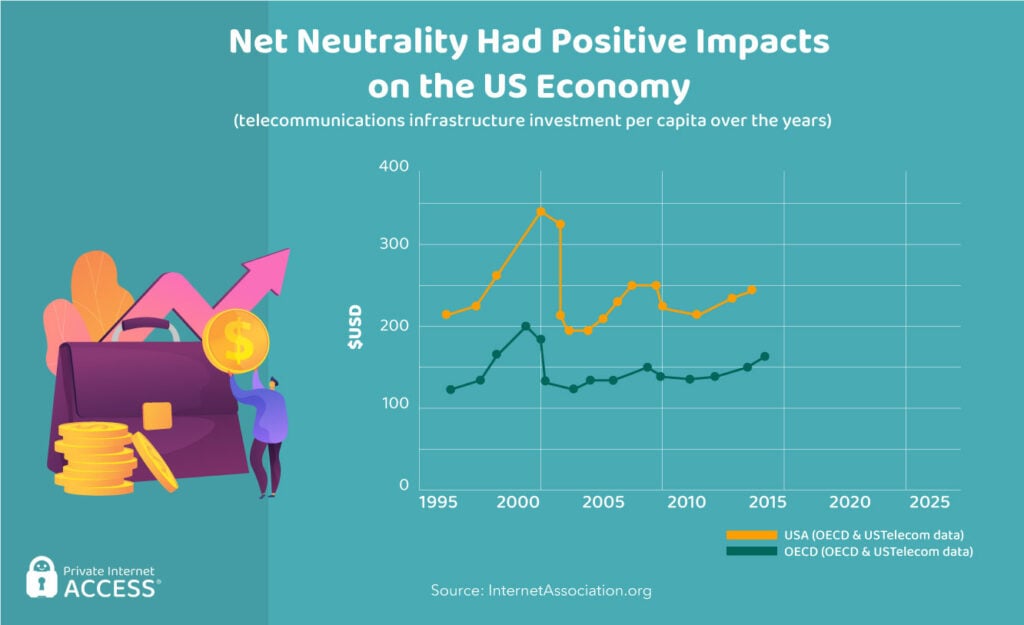

In its first seven years (since 2010), net neutrality in the US had several positive impacts on the American economy. It facilitated a healthy telecommunication sector and helped fuel significant levels of innovation, economic growth, and job creation in the technology sectors.

Despite concerns, it caused no economic harm, neither as a result of the FCC’s 2010 Open Internet Order nor its 2015 Net Neutrality regulations.

Net neutrality had no negative effect on telecom infrastructure investment, broadband infrastructure investment, or cable infrastructure investment.

It also had no industry harm as collective corporate net income and equity had increased steadily after 2008.

No negative effect was observed on telecom providers’ industry innovation either.

Finally, there was no evidence of capacity or bottlenecking issues for the telecom industry.

The Bottom Line

In a society that is becoming increasingly more globalized, interconnected, and internet-dependent, online freedoms have never been more important. The issue pervades region, class, gender, age, and literacy level.

Sadly, access to the internet isn’t the same for everyone and it’s often the victim of political, religious, social, educational, and infrastructural constraints. Some people don’t have access to the internet at all.

Hopefully, as our societies advance, the playing field will become levelled for everyone, everywhere, making internet freedom an equal right around the world.