A comparison of two very different European privacy cultures

I recently moved from Stockholm, Sweden to Berlin, Germany. It is quite illustrative to see how different these privacy cultures are, and in particular, the expectations from authorities on both sides on an expat that tries to bridge these cultures. The result is often rude, unthinkable, and downright illegal in at least one location.

In Sweden, you’re assigned a number at birth. This number is not just more important than your name when dealing with all authorities, it is your name when dealing with any and all authorities. Think of it as a social security number that extends to driving licenses, healthcare, taxes, housing, unemployment benefits, passports, voting, and anything and everything. Furthermore, this number is public. And since it is public governmental data, anybody may call any agency of any branch in the government, and ask any employee about anybody’s ID number, and they are required by law to provide it without being allowed to demand anything else first, like the name of the caller.

My Swedish personal ID number is 19720121–4819. My year, month, and date of birth, followed by a serial number assigned to babies born that day (481), followed by a Luhn checksum digit (9). I was tagged with this number literally the moment I was born. It was on a heavy plastic band around my ankle at the maternity ward, attached immediately, not entirely unlike a shackle intended to be carried for the duration of the baby’s life.

Seeing how people are not their names in Sweden, but this number, a lot of businesses use it to refer to their clients as well. You can’t sign up for banking services with your actual name in Sweden, for example; only with your number. You log on to the bank using this personal ID number, not with your name. Yes, I am serious. Same thing with any insurance company, car dealership, et cetera. Contracts are written with parties specified as the people’s ID number, with their actual names being secondary. This includes things like your employment contract.

This was a contrast when moving to Berlin, Germany. Germany compartmentalizes information to the extreme within its government.

When first arriving, you get your tax identity number. I figured this would be somewhat like the Swedish number, used everywhere, but no: it’s used not just only toward the tax authority, but only against some parts of the tax authority. Other authorities are expressly forbidden from having anything to do with this number, for the literal reason to make it impossible to coordinate data against you. I was then assigned a tax number (different from the tax identity number) and a sales/VAT tax number (different from the two previous ones) for dealing with the tax authority.

It follows that no other authority in Germany would ever ask for this number. They all have their own. They’re designed to have their own. The other day, I applied to have a health insurance number assigned, again separate from all the others. The entire system is designed to make it hard or impossible to automate collection of data on residents. It follows that a bank in Germany would never, ever, ask for your tax identity number; doing so would be rude beyond the conceivable.

So you can see the culture clash when my previous Swedish banks note that I have moved, and mumble something about federal EU regulations blah blah, and demand that I send them my German tax identity number.

This is the fourth reminder I just got. They’re sending me these a couple of months apart from Sweden, and note that in order to comply with federal European Union regulations, I must provide my German tax identity number to the Swedish bank within fourteen days. I keep ignoring them, as I know full well that this cannot possibly be European Union law, as the tax secrecy in Germany goes all the way down to the German Constitution. Germany takes privacy extremely seriously, and Berlin even more so: this is a location, where people literally have Nazi and Communist rule in living memory (up until 1990), and are determined to never make anything like that happen again.

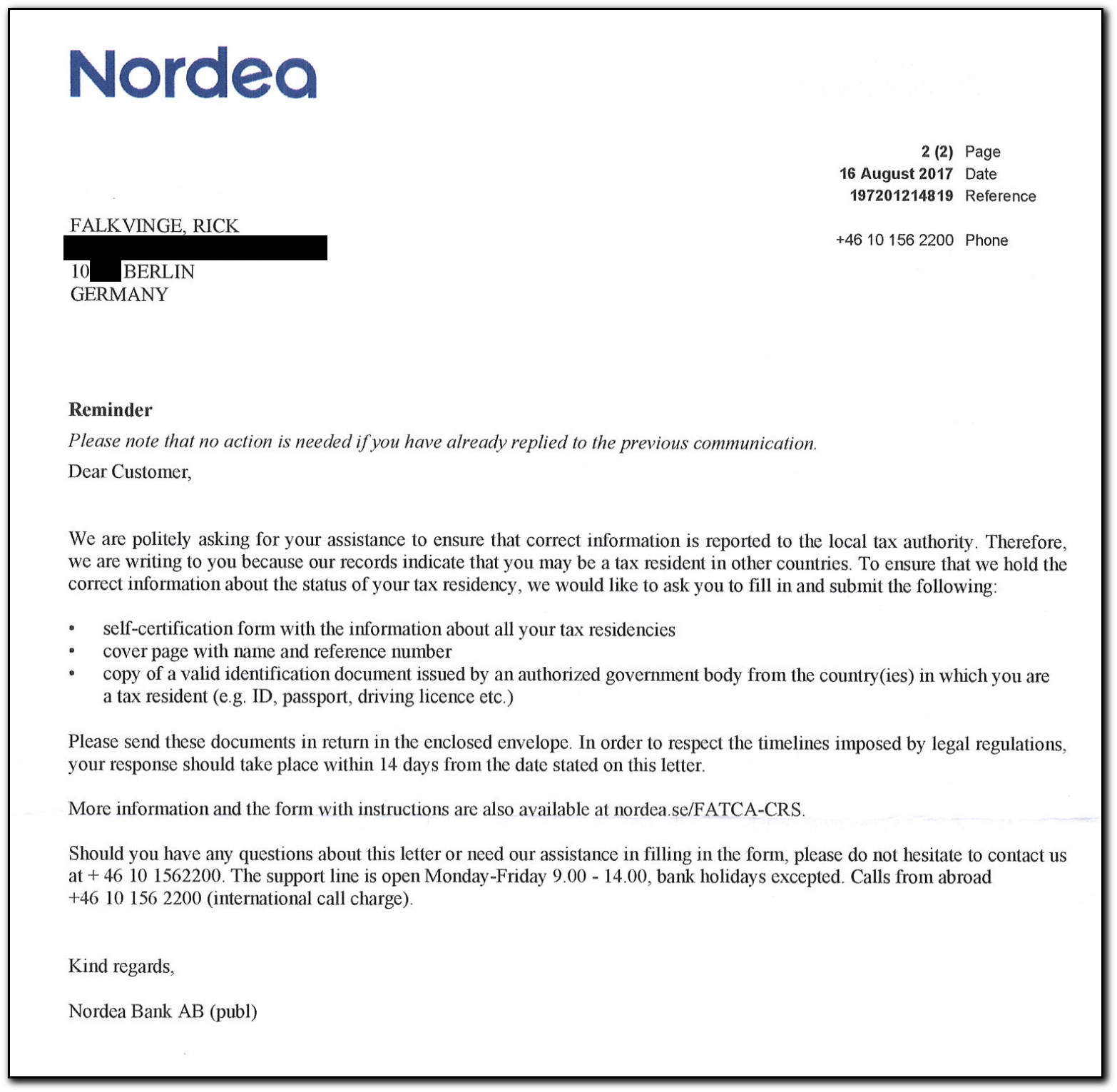

The actual letter. Note the Swedish personal ID number used as communications reference top right; my name and address are only used as a postal address, not as a name.

In case it’s not already clear, in Berlin and Germany, this is unspeakably, unforgivably, inconceivably rude communication from a bank. It would be as inconceivable as asking you to provide your skin color for the bank’s records.

I actually responded to the Swedish bank’s persistent reminders this time, and sent them a letter with this wording:

I have to say that Nordea is persistent. I think this is the fourth reminder I receive every few months that I have to return your form, where I am required to fill in my German tax identity number and return the form within 14 days.

Seeing how you have my address, you also observe that I live in Berlin. This is a city where people, who are still alive, remember what it was like living under both Nazi and Communist rule. Therefore, things are a little different than in Sweden. A little more thoughtful. Significantly wiser.

For example, it is completely unthinkable that a bank would request a tax identity number. That is something that only the German Tax Agency has business asking for. And the German tax secrecy goes all the way down to the German Constitution.

The fact that a bank requests a tax identity number, as you do, is as rude and unthinkable here in Berlin as if a bank in Sweden would ask for your skin color or sex habits.

So by all means, continue to send reminders to provide my German tax identity number, because you will never get it. I also note that your request for this form must be returned within 14 days is a legal requirement under Swedish law. That law, of course, does not apply in Berlin either.

Sincerely,

But the key takeaway here is that the Swedish bank is probably not even aware that it is being unforgivably rude when requesting my German tax ID number. After all, it can ask almost anybody for my equivalent Swedish number. The Swedish bank is just doing as it’s always done, and as it is told to do by the Swedish government. I hold it unlikely that Nordea is even realizing what a faux pas they’re committing.

And therein lies the real privacy lesson here: the really bad things happen when people just take the absence of privacy for granted, and do as they’re told. It requires a contrast to somebody who does things right to realize that this is even happening.

(This extreme transparency of governmental records in Sweden does have its advantages, though. During the depressing times when there was actually governmental movie censorship for grown-ups, in order to reduce depictions of violence (not sex and nudity, nota bene, but violence), any and all movies submitted to the Governmental Cinematographic Censorship Bureau were public governmental documents. As such, people with knowledge of how the system worked would walk straight into the Censorship Bureau and ask if they could please see this movie that was 18+, except they wanted to see it uncensored. Typically, some front door person would ask for ID to certify their age for watching the movie, which they would refuse to show and demand to see a supervisor, and that supervisor would immediately say that they’re not allowed to even ask for ID, apologize for that happening, and promptly direct them into a viewing room where they could see the requested public governmental document without restriction.)

Privacy remains your own responsibility.

Comments are closed.

The solution: do not tell your new address to the officials in Sweden when you move. If you are not living in the country anymore, it is none of their business where you live. In fact, why even tell them that you have moved?

I think this “government must be in control of everything” mentality we have in the Nordic countries (exemplified by the universal ID number) is going to blow up on our faces some day when there is a government that is not so nice anymore and it has access to all information of all people in the country.

“it’s used not just only *against* the tax authority” . Swenglish? :-)

Didn’t the Germans give you the VAT number for that? It’ probably on VIES… http://ec.europa.eu/taxation_customs/vies/vieshome.do

Yes, the VAT ID was one of the three identities I got from the tax authority. Since this is a global audience, though, I described it as “VAT/sales tax number” above, to make it more generally understandable.

Yes, wouldn’t that satisfy the Swedish bank’s need?

Note that in The Netherlands, the VAT number is made up of your ‘civilian service number’ with a B for business and a counter for bankruptcies. While the government teaches people to mask this number and birthday on copies, they also publish it on the chamber of commerce’s website.

On a separate form, not shown here, they’re quite deliberate about what identity number they expect, and it’s not the VAT id but the key, main, tax identity number.