Freedom of speech, surveillance and privacy in the time of coronavirus

The situation concerning the Covid-19 coronavirus is serious, although it is not yet clear whether it will develop into a pandemic affecting billions of people worldwide. The story so far touches on most of the central themes of this blog. For example, we know that the Chinese authorities wasted valuable time trying to suppress news about the possible outbreak of a new virus, instead of acting swiftly to limit its spread. Given China’s record of obsessive control, that’s no surprise, but what is unexpected is the reaction of the public there, which has called for greater freedom of speech after the death of the whistleblower doctor who tried to raise the alarm:

The outpouring of grief quickly turned into demands for freedom of speech, but those posts were swiftly censored by China’s cyber police. The trending topic “#we want freedom of speech” had nearly 2m views on Weibo by 5am local time, but was later deleted.

Once the Chinese government admitted that there was a dangerous threat facing the country, it reacted extremely, shutting off entire provinces, and forcing tens of millions of people to stay in their homes. Generally this kind of house detention applies only to activists, so this move allows Chinese citizens to understand and experience what their government’s repression of others is like.

Physical lockdowns are not the only response from the authorities. The Chinese government has also repurposed its famously comprehensive surveillance system to look for anyone who might be infected, drawing on local technology firms. The facial recognition company Megvii says its new “AI temperature measurement system” uses thermal cameras to spot people with a temperature, and then applies AI to identify them. The surveillance camera supplier Zhejiang Dahua claims it can detect fevers with infrared cameras to an accuracy of 0.3°C. Another Chinese AI company, Sensetime, says that it has built a system that can identify people wearing masks.

There are also various high-tech approaches to dealing with people not wearing masks. The Chinese Internet giant Baidu has developed a facial-scanning program that uses artificial intelligence to identify people without protective masks, and released it as open source. Some regions have deployed a police-operated drone equipped with a camera and loudspeaker, which spots people without masks, and then tells them loudly to put one on.

The “Close Contact Detector” app tells users if they have been near someone infected or suspected of being infected. The state-run news agency Xinhua said that the app was jointly developed by government departments and the China Electronics Technology Group Corporation, and drew on data from health and transport authorities. The Chinese railway system’s requirement for people to use their real name when booking a ticket means that it can provide a list of people sitting nearby a person who is a confirmed or suspected coronavius case. The makers of Close Contact Detector said that they received 100 million queries within the first two days after its launch. Privacy doesn’t seem to be much of a concern. Another important issue is what will happen to all this data when the coronavirus crisis is under control.

Yunnan province is taking a different approach, but one which also raises privacy issues. Residents there are required to scan a code using a mini-program on the popular Weibo/WeChat system when they enter and leave public places. As the South China Morning Post explains:

The mini-program, whose name roughly translates as “Fight the coronavirus in Yunnan”, requires users to enter their phone number and receive a verification code to register. After that, they scan the “in” and “out” code when visiting public places such as airports, railway stations, subways, bus terminals, shopping malls, supermarkets, residential areas, as well as hospitals and pharmacies.

The idea is to make it easier to trace people who may have had close contact with somebody confirmed or suspected of having the coronavirus. However, people have pointed out that many elderly people do not have smartphones, and so cannot use the WeChat mini-program. In addition, making everyone scan a code to enter and leave public places is likely to cause congestion at entrances and thus increase the risk of infection.

In Hangzhou, a different approach has been adopted. Residents are asked to use a smartphone-based program to report on their health status. Only those with a “green” status, displayed as a QR code on their phone, are allowed to enter. However, the code is decided on the basis of self-assessment of their symptoms and travel history. That makes it easy for people to cheat by omitting tell-tale signs of infection. Despite this clear loophole, the Chinese government has instructed the tech giant Alibaba to explore the nationwide roll-out of the rating app.

It seems appropriate that China’s surveillance apparatus should help combat a new disease whose deadly impact is due in part to the China’s obsession with control. However, the situation raises a number of questions. For example, will the technological measures being deployed to tackle the epidemic be left in place after it has been brought under control? Might the Chinese authorities claim that they are needed to prevent the next new infectious disease from spreading as rapidly as it has done on this occasion?

A key issue for the rest of the world is: how will countries without such thoroughgoing surveillance respond if the coronavirus spreads widely there? Will they cope anyway, through traditional epidemiological procedures for tracking down infected individuals and their contacts, or might they be tempted to use it as an excuse to bring in China-like systems of control?

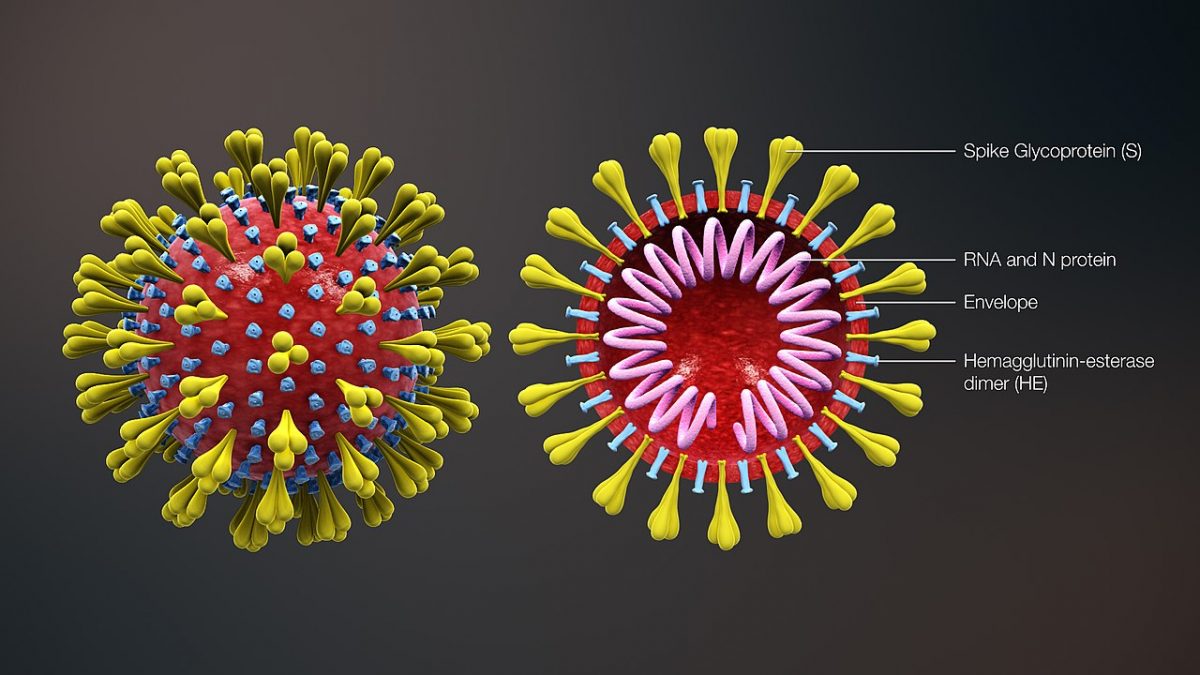

Featured image by Scientific Animations.