Phishing, Smishing & Vishing: What You Need to Know & How to Protect Yourself

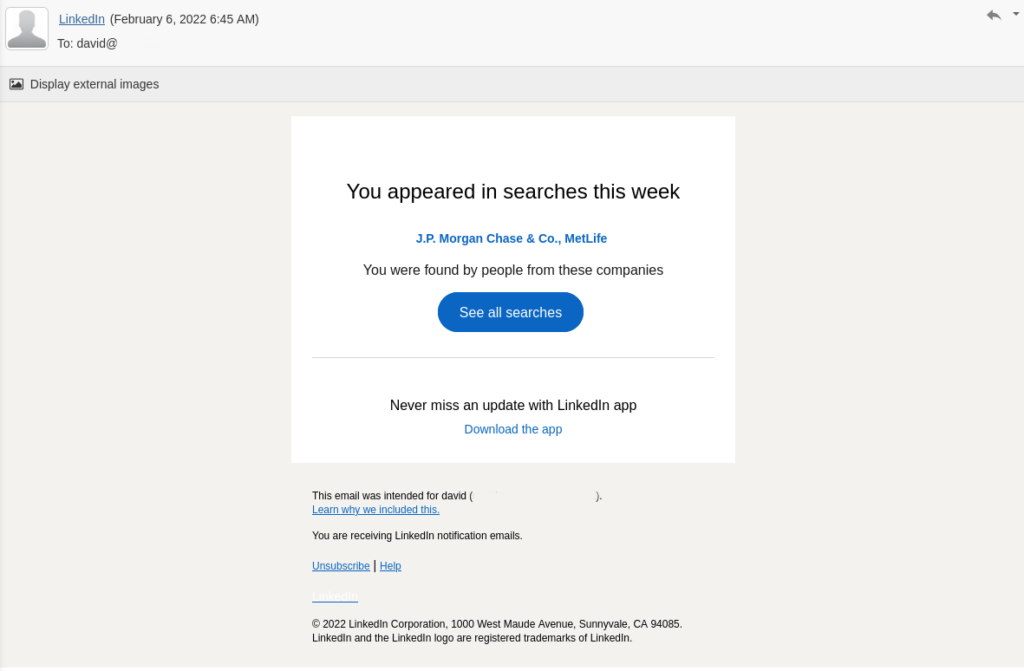

My career is about to take off — at least it is if I was to believe the number of companies looking at my LinkedIn profile over the past few weeks.

On an almost daily basis, the business networking company — helping professionals connect and show off their work history — has informed me that execs from Dell, JP Morgan, Metlife, and Philip Morris International have been checking out my info. I’m in demand and can probably expect to receive unsolicited offers for jobs with a six-figure salary any day now.

It would be great — if it was real.

But I don’t use LinkedIn — for reasons to do with privacy, surveillance, and a general reluctance to entrust my details to a company that habitually loses customer data. The messages, therefore, could not have been sent to me by LinkedIn. So who sent them, then?

The quick ego boost I experienced from the email subsided as I realized that no one was particularly interested in my career, and that I’d almost been hooked by a phishing scam.

What is Phishing?

Criminals on the internet are not a new phenomenon and they have a number of aims. The most obvious one is to try and steal money from a victim’s bank accounts. Other criminal groups may try to use a victim’s account to gain access to a larger organization. Often, they try to take control of a victim’s machine in order to encrypt and ransom the contents, or to suborn it into a larger criminal enterprise.

But hacking other people’s computers is difficult, time consuming, and potentially dangerous — especially if criminals are indiscriminately targeting a large number of people.

The easiest way to get hold of an individual’s username and password is to ask them; there’s no simpler way of installing malware on a victim’s machine than giving them a button to click so they can download it themselves.

Phishing (pronounced “fishing”) involves sending deceptive messages that persuade potential victims to hand over their credentials or visit sketchy webpages. To be successful, the messages must be believable and make victims want to click through.

Spear phishing is a more refined form of phishing that targets specific individuals or groups of people. Criminals spend time studying individuals, gathering data on them in order to send highly specific messages that they’re more likely to open. Social media is a great source of information when crafting emails for spear phishing.

How Does Phishing Work?

If I had clicked on any of the links within the email sent to me, it’s likely that I would’ve been redirected to an exact replica of the LinkedIn login page, with a custom URL alerting criminals that I’d opened their message. As soon as I visited the dummy webpage, they would’ve known it was me, because I was the only person who was sent that exact URL.

I would’ve entered my username and password, and after that, I may even have been redirected to the genuine LinkedIn login page. At that point, I’d probably be slightly baffled as to why I had to log in twice, and even more confused to find that no one had been looking at my profile at all.

Meanwhile, the username and password I had entered would’ve been recorded by the scammers and tied to my email address by the tracking ID or the specific URL.

It’s a mistake to think that scammers can’t do much with a LinkedIn ID and password. They can gather details of your professional contacts, your job history, and your education; they can find out your legal name and which company you work for. If they’re lucky, they can gather enough personal information to successfully impersonate you.

If the scammers are really lucky, they’ll hit someone who uses the same username and password for multiple online accounts. If this happens, the best possible outcome is that your email account becomes the source of fresh email addresses for more phishing attacks. And the worst? They get access to every platform and site that you’ve used the same credentials for — whether that’s your Facebook account or online banking app.

Different Types of Phishing

Phishing via email is the most common type of attack; it’s super-easy to do and can be carried out at no cost, either by using free-tier VPS, hijacking a mail server, or even someone’s home PC — but it’s not the only method.

Other phishing attack methods include “vishing”, which involves a phone call from a person pretending to be a trusted institution such as a bank. The criminal will ask you to confirm private details such as your account number, sort code, and card information, often telling you that (ironically) your account has been compromised.

Scammers also commonly send phishing text messages, which is known as “smishing”. These text messages usually impersonate reputable organizations such as delivery services, with a link to track your parcel or rearrange your delivery.

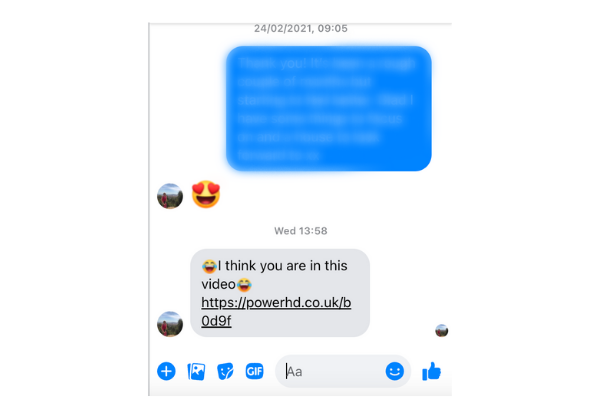

Or, they might hit you with a message from someone you trust by hacking their account, such as your family member on Facebook Messenger. Messages almost always include a link for you to click.

Both vishing and smishing employ paid-for network services, as it costs to make a phone call or send a text. But neither are nearly as common as email phishing.

How Do Scammers Get Your Details?

The easiest way for criminals to obtain a list of valid email addresses is to buy them.

Different groups of hackers target organizations with a large user base to obtain as much information as possible. LinkedIn isn’t the only platform falling victim to cybercriminal attacks, but their record for upholding data security over the past decade is less than impressive.

More than 100 million sets of account details were stolen in 2012, followed by a further 500 million in May 2016, and 700 million a mere two months later, including “full names, gender, email addresses, phone numbers, and industry information”.

Scammers can also get hold of your details if they appear in the contacts list of a compromised account — either personal or business — or if your email address appears anywhere on the web. My email address is viewable on two of my personal websites, which is, I assume, where it was scraped.

Phone numbers for vishing and smishing attacks are obtained in a similar way. Most people provide their phone numbers whenever they sign up to an online service. When that service is inevitably hacked, phone numbers can be revealed along with the other details. These are then packaged and sold to scammers.

Another way for hackers to target you is by combining common names and last names with numbers and well-known email providers. If your email address is based on this format, there’s a good chance you will be targeted by hackers, even if they have no other information about you; for example, sending out emails to ‘[email protected]’ or ‘[email protected]’.

Email accounts have more value to criminals if they’re active. An easy way for hackers to tell if an account is active is to have an email load trackers from elsewhere on the internet. These trackers can be as simple as an image with a unique code that is matched to an individual recipient.

Most emails aren’t just plain text and attached image files; they’re actually HTML pages. As such, they’re able to drag in components from elsewhere on the web and display them in your email inbox. This saves on resources as hefty image files can be hosted on a remote server rather than sent in the email itself.

When the images are displayed, a request is sent from your machine to the server, requesting the image file; this action can be logged by the remote server admin. If images in emails are set to load automatically, hackers will know that the account is active as soon as the email is opened, even if no other action is taken. Marketers do this and even your bank does it — the difference is the email you receive from them is legitimate.

Why Do People Fall For Phishing Attacks?

Phishing attacks are designed to fool people. If you have fallen victim to one, you shouldn’t feel too bad about it; they’re meant to trick as many people as possible through plausibility, and will either exploit their victims’ curiosity or fears of their own safety.

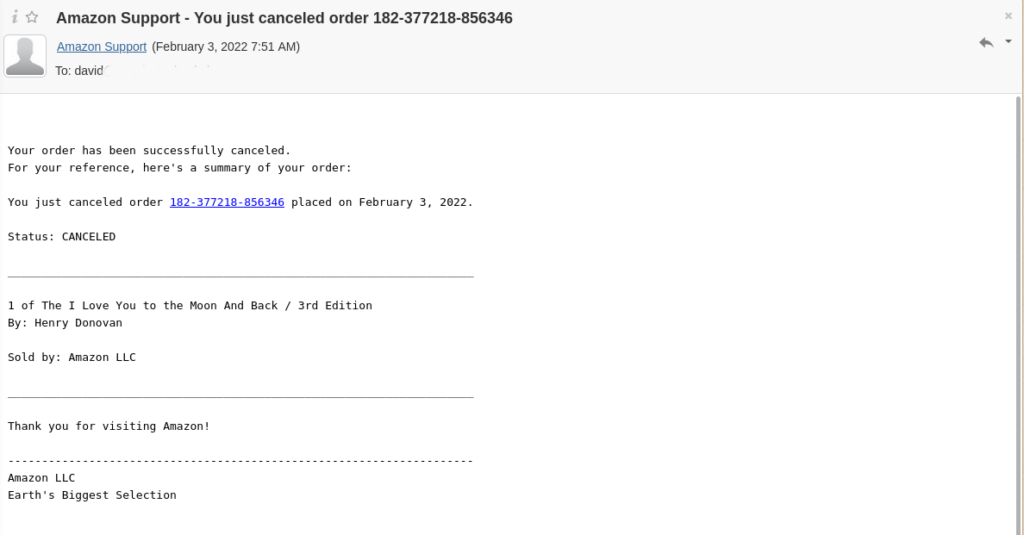

My curiosity was piqued because I wanted to know who had been looking at my non-existent LinkedIn profile. Even though I know full well that I don’t have access to the platform, I almost fell for the hacker’s bait. Another phishing email I received recently told me that an Amazon purchase I had made had been canceled, despite never making a purchase.

This appeals to curiosity — the recipient wants to know which item has been canceled. And then they’d probably fear that someone has accessed their Amazon account to purchase something. The temptation to feverishly click through can be overwhelming.

How to Avoid Being Caught by Phishing Attacks

Not every email you receive is sent with the intent to trick you into revealing personal information, but it’s a good idea to pretend that they are.

It’s good practice to have image loading turned off by default — if you accidentally open a phishing email, scammers will know that the account is active. And if you open it while connected to your home WiFi and not connected to a VPN, they’ll know your IP address, too.

The email itself will also contain a number of giveaways, depending on the sophistication of the scammer. If the email is impersonating a well-known company, spelling mistakes in the text are a giveaway.

Other easy-to-spot factors that indicate an email is not from a legitimate sender include:

- Odd use of paragraphs: Corporate emails are carefully crafted by professionals — it’s unusual to find formatting errors.

- Overly formal language: “Dear Sir or Madam” or ”Dear Customer” shows the sender may not know your name and you’re unlikely to have an account with them.

- Low quality images: Sending emails may be free, but images can take up a lot of bandwidth — using low resolution images helps keep spammers’ costs low and their activity undetected.

- Calls to action: Marketers use artificial urgency in order to push potential customers into buying something — spammers and scammers do the same. They want you to do something, and do it now.

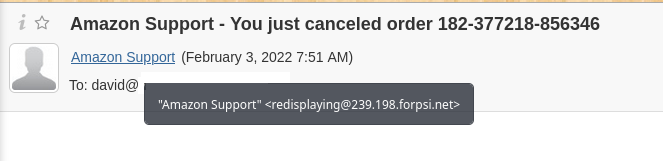

After reading the text, you should check who the email is really from. You can see in the below image that the sender is ‘Amazon Support’, but hovering over the name reveals that the sender’s address has nothing to do with Amazon.

Even if the sender’s email seems legitimate, you should examine any links before you click on them. Hovering over links in the email body will show the true address at the bottom of your browser window. It should match the sender’s supposed source — links in an email from Amazon, for instance, should appear as an Amazon domain.

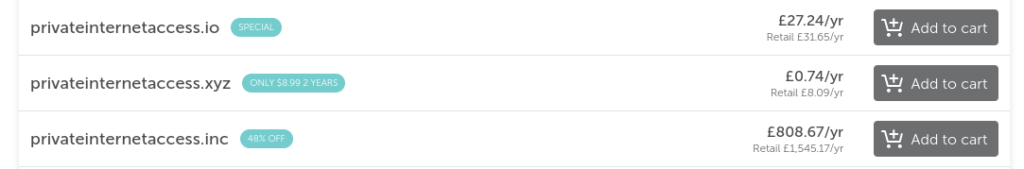

You should also be careful of substitutions — Amazon is not the same as Amaz0n, for example. Scammers can buy second-level domains for a mere few dollars, allowing them to impersonate reputable and trustworthy organizations.

Even if everything within the email appears to check out, you should still exercise caution.

If Amazon, PayPal, LinkedIn, or any other company is sending you notifications, those notifications will be there if you log into your account directly. Open up a new browser tab, type in the address, and see if you can see the notifications when you log in.

Spotting Vishing and Smishing Scams Isn’t as Easy

Sitting at your desktop computer, spotting scam emails is fairly straightforward. You have a nice big screen on which to inspect formatting and a mouse with which you can hover over links to gain more information without actually clicking on anything.

On phones, you’re very limited as to what information you can easily access and when your mobile is ringing, you have a limited amount of time to decide whether to answer it or not.

If the call is from a freephone or unknown number, you should never assume that the caller is who they say they are — in fact, it’s best practice not to pick up at all. Instead, Google the number and find out who it belongs to. If it’s your bank or energy company, call them back on the number listed on their website.

Remember, just because the number that appears on your screen does belong to your bank, it doesn’t mean that it’s really your bank calling you.

Scammers are able to ‘spoof’ caller IDs, meaning that the number showing up on your screen isn’t the one actually calling. This doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t answer the call, but you should be extra careful when giving away information.

Some signs that a phone call is from scammers include:

- Asking you for your account credentials such as logins, passwords, or account numbers

- Using an unwarranted sense of urgency to panic you into taking action and handing over your details

- Seeming too good to be true — no-one has deposited a million dollar check into your account

Numbers attached to text messages can also be spoofed, so there’s no guarantee that the parcel tracking message you’ve received from FedEx is genuine.

Do not, under any circumstances, click on links in text messages — you can never be 100% sure who they’re from or where they lead to.

The Bottom Line

The world is full of cybercriminals who want to trick you in order to gain control of your accounts. They’re able to convincingly impersonate other people, organizations, and businesses.

Such scams appeal to curiosity and fear, often creating a false sense of urgency in order to get you to click on links, open emails, or answer phone calls.

To keep yourself safe, you should:

- Make sure that image loading is turned off in emails.

- Never assume the sender is who they claim to be.

- Never click on a link from within an email.

- Don’t ever give away personal information over the phone.

- Don’t click on links within text messages.

- Always assume that any unsolicited contact is a phishing attempt.

And remember, as much as you’d like to believe you’ve won the lottery without ever buying a ticket — you haven’t.