Privacy is constantly under threat; here are ways communities can help to protect it locally

Stories about privacy have a depressing tendency to be about its loss, and the increasing threats to it in the future. Perhaps we need to spend more time thinking about how to protect it, to prevent the loss and head off the threats. That’s easier said than done, since the latter come from many quarters, and take many forms. But even if it is not possible to draw up a complete and definitive approach to defending privacy, it is worthwhile looking at what has worked in the past in order to bear it in mind for future battles.

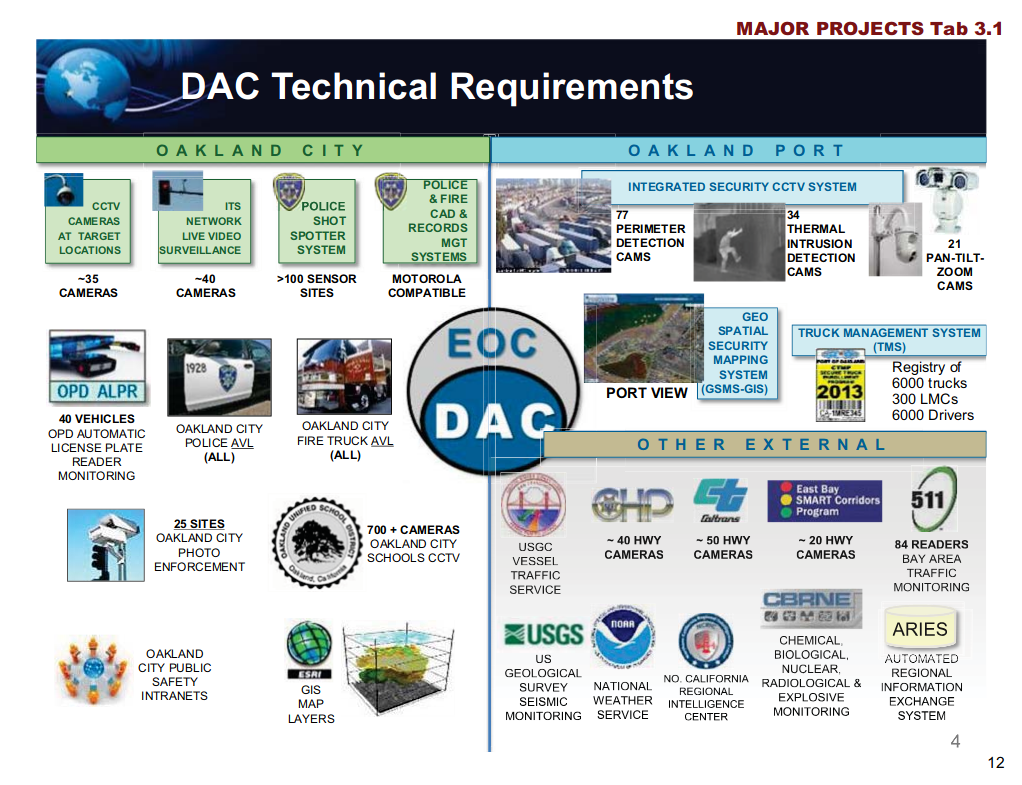

One episode in the annals of privacy has been taking place in Oakland, California. Back in 2013, Oakland residents discovered that the City of Oakland City Council was intending to approve a second phase of a port security monitoring system. This entailed extending Oakland’s Domain Awareness Center (DAC) into a city-wide surveillance apparatus that would have combined feeds from cameras, microphones, and other electronic monitoring assets throughout the city – see DAC Technical Requirements slide above for details.

An Ars Technica story from the time has a vivid report on a tumultuous city council meeting where the Oakland City Council unanimously accepted a $2 million federal grant to create the extended DAC. The council agreed to add some rudimentary privacy protections to the scheme, but many local activists felt these were inadequate. This led to the creation of the Oakland Privacy group, whose efforts prevented the city-wide rollout of the DAC, and brought about the creation of a city privacy advisory commission, which has continued to play a very active role in defending privacy in the area.

The Electronic Frontier Foundation has just published an interview with Brian Hofer of Oakland Privacy and the City of Oakland Privacy Commission, about the group’s work. Based on practical experience it offers a number of valuable tips about how communities can defend privacy locally. Perhaps the most powerful method is demanding real transparency from the authorities. Hofer is quoted as saying:

“It’s very hard for law enforcement, or anyone else, to say that transparency is not good, or that there shouldn’t be any oversight, or that there shouldn’t be public hearings. So we have these arguments that people would have a hard time defeating, and have been able to bring this approach throughout the entire Bay Area.”

In addition to demanding transparency and oversight as a matter of course, it is important to start discussing early on the impact of surveillance plans on privacy:

“The Domain Awareness Center was shoved down the public’s throat before they even knew what it was, and before we discussed privacy. We’re now flipping that on its head. We’re having the public conversation at the beginning, about whether this is appropriate or not for the community, and if so how should it be regulated? What sort of use policy is going to govern it?”

Those are fairly obvious actions to take. But Hofer mentions another important approach the Oakland Privacy group has adopted that it would be easy to overlook:

“We’re maintaining oversight and then also forcing law enforcement to come back after the fact and report on how they used it. They have to demonstrate the efficacy, maybe make amendments to the policy if there have been any violations, and actually demonstrate that the equipment is achieving its purpose.

I suspect that some of this equipment is snake oil, and it’s not going to be able to stand up to scrutiny once it has to start demonstrating the hard numbers that should go with it.”

It is often very difficult to stop surveillance projects completely, since the authorities shamelessly play on people’s fears to push them through. However, as with transparency, it is very hard for supporters of the projects to argue that it is not legitimate to ask whether the systems achieve their stated goals once they are up and running. Without a meaningful review of the implementation, approval of a project would amount to spending money without worrying about whether it was well spent. Calling for reports on its real-world efficacy should be uncontroversial and supported by all political parties.

Unsurprisingly, Hofer says that social media allows local organizations to raise awareness and to ask people to attend important meetings. He also notes that once you show people how to keep an eye on council agendas, or to submit public record requests, people will do so. That suggests one potential action for privacy activists, both in the US and more widely, is the creation of online resources laying out in simple, approachable language, the kind of rights people have to attend key meetings and ask questions, and how to submit formal freedom of information requests, or even to write to local and national politicians.

Many people have never done any of those, and yet they are all inherently quite straightforward. But not knowing how – or being unaware that they are things ordinary people can do – is often a barrier to participation. Online information taking people through the process step by step would do much to remove those obstacles.

The Oakland Privacy site already has some valuable resources, but they are not designed specifically to encourage the wider public to use them in a targeted way to defend privacy. Perhaps the time has come for activists to get together and create a general wiki with that goal in mind – the EFF would be an obvious host and facilitator for this. It wouldn’t take much effort, especially if shared out among the people already making use of these opportunities. But it could have a dramatic impact on the scale of proactive privacy work, something that is urgently needed.

Featured image by Port of Oakland.