The UK home secretary still doesn’t know how encryption works, and she’s not ashamed

Railing against the use of encryption by criminals has always been an exercise in futility, but it’s a great way to sound tough. What better way to assert your power as a law-enforcer than by demanding the impossible?

The problem is, there’s a line between swagger and overt foolishness, and for some reason politicians are increasingly deciding to hurl themselves over it — witness, for example, Australian prime minister Malcolm Turnbull declaring earlier this year that “the laws of mathematics are very commendable but the only law that applies in Australia is the law of Australia.”

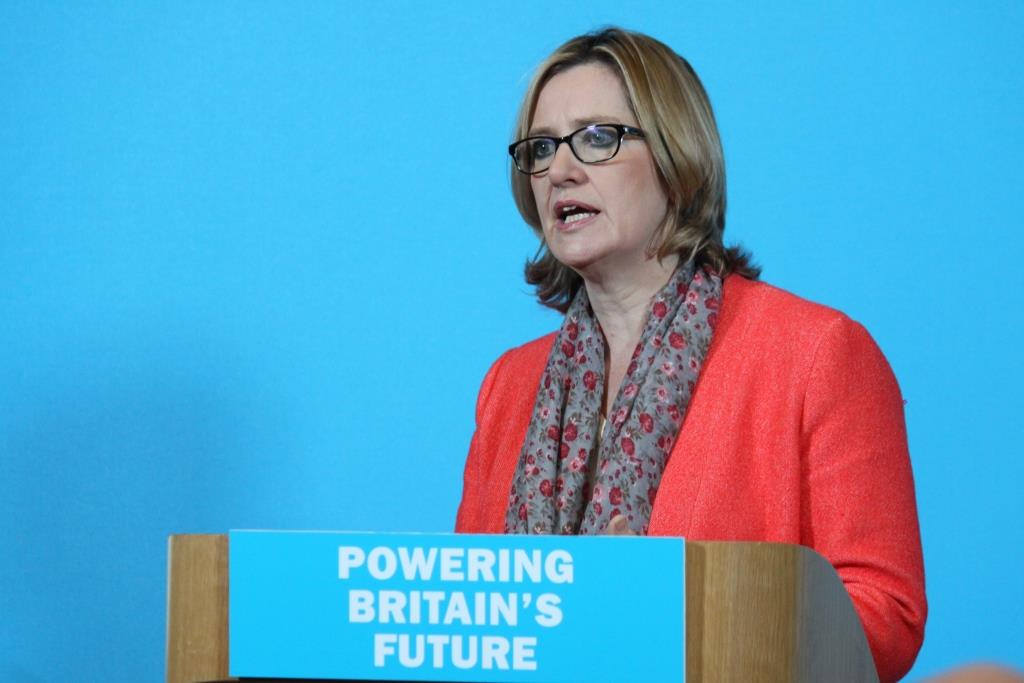

The British home secretary, Amber Rudd, has now decided to follow the path of Turnbull by proudly announcing not only that she doesn’t understand how end-to-end encryption works, but that she does not need to understand it in order to fight it.

Speaking at a fringe meeting at the Conservative Party conference, Rudd said:

“I don’t need to understand how encryption works to understand how it’s helping — end-to-end encryption — the criminals. I will engage with the security services to find the best way to combat that.”

That gem came in response to a question from someone in the audience about whether she understood what she was talking about, after she said she didn’t want to ban end-to-end encryption and also didn’t want to put back doors in encrypted communications services, but she did want to “allow easier access by police and the security services.”

Rudd also said:

“It’s so easy to be patronised in this business. We will do our best to understand it. We will take advice from other people but I do feel that there is a sea of criticism for any of us who try and legislate in new areas, who will automatically be sneered at and laughed at for not getting it right.”

Rudd’s frustration is entirely understandable. It must be very irritating to declare that up is down, and in is out, only to have people laugh at you and suggest you don’t know what you’re talking about.

To be fair, it is not reasonable to expect senior politicians to understand all the technicalities of everything they deal with, day in and day out. However, it is reasonable to expect them to listen to the experts who do understand these things, and to have the humility to evolve their own ideas in the face of those experts’ evidence.

Perhaps Rudd could take a cue from U.S. senator Lindsey Graham. When the FBI was sparring with Apple over access to a terrorist’s iPhone a year and a half ago, Graham instinctively waded into the debate on law enforcement’s side, asserting that “this iPhone was used to kill Americans.”

But then Graham talked to experts in the intelligence community, who told him that forcing Apple to essentially backdoor the iPhone would be A Very Bad Idea. “I will say that I’m a person that’s been moved by the arguments about the precedent we set and the damage we might be doing to our own national security,” Graham conceded.

One does not have to be a technical expert to appreciate the following facts about end-to-end encryption. By its very nature, it stops the service providers from being able to decrypt the messages its users are sending, which means they couldn’t give law enforcement access even if they wanted to. The only way to make this not the case is to put a backdoor in the system that essentially breaks the end-to-end nature of the encryption. And this flaw in the system will necessarily make it weaker, while making service providers and users in countries with oppressive regimes vulnerable to those regimes’ legal orders.

In short — and in words that must surely be very familiar to a British government that is currently bogged down in messy Brexit negotiations — you can’t have your cake and eat it. Either you ban or subvert end-to-end encryption, or you accept that you need to leave it alone because everyone uses the same technology, and it’s impossible to be selective about who benefits from the protection it provides.

In any case, Rudd must surely be aware that the way round the encryption problem is to hack into suspects’ phones, in order to read what they’re typing and see what’s on their screens. After all, she was already home secretary when the UK’s Investigatory Powers Act passed late last year, allowing the authorities to do precisely that.

But moving on from one of history’s most pointless and repetitive debates wouldn’t give her the talking points she needs to sound tough. And we can’t have that, now, can we?

Featured image from UK Department for Energy and Climate Change, shared by CC-By-ND-2.0.