Top court rules UK mass interception of fiber-optic cable traffic violates the right to privacy: a victory, but how big?

Five years have passed since Edward Snowden’s revelations about the scale of surveillance by the US and UK shocked the world. Things have gone rather quiet on that front now, partly because there have been few new releases of documents from the Snowden hoard. But in the background, many privacy groups have been quietly working away, using the information released by Snowden to hold governments to account. One of those efforts has just come to fruition: the European Court of Human Rights has ruled that the UK’s use of mass surveillance, as revealed by Snowden, violates the fundamental right to privacy.

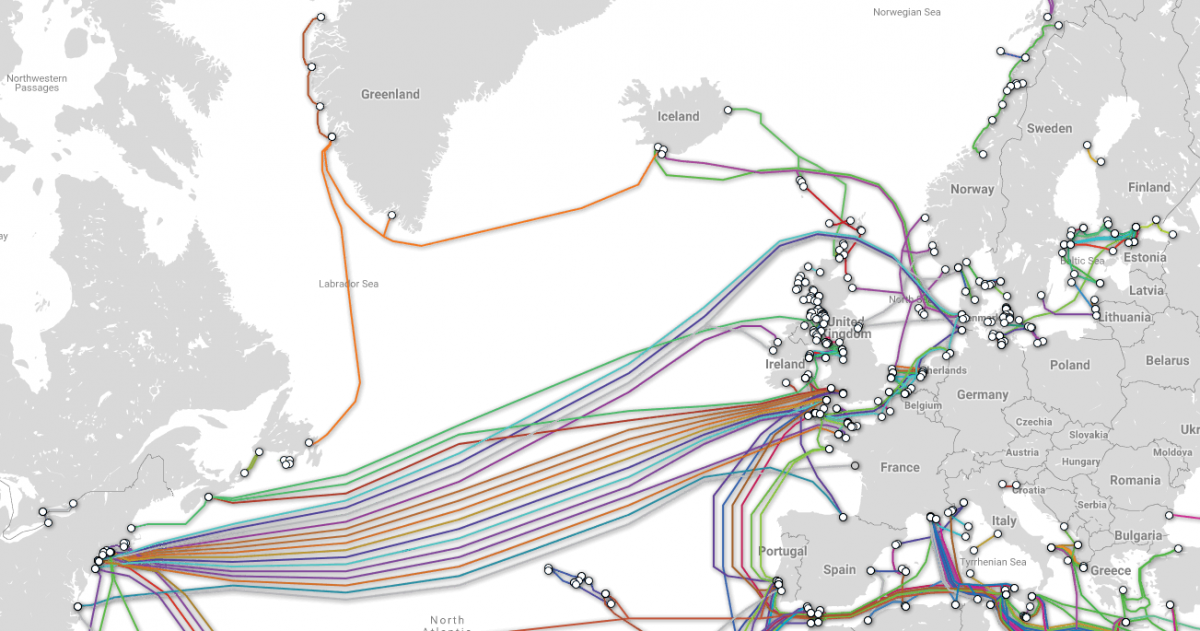

The case concerned some of the earliest documents from the Snowden leaks. They disclosed that the UK was routinely tapping into a large proportion of the fiber-optic cables that criss-cross the world carrying data traffic. With refreshing honesty, Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ), the UK’s equivalent of the US NSA, named these surveillance programs “Mastering the Internet” and “Global Telecoms Exploitation”.

According to The Guardian article that broke the story: “Each of the cables carries data at a rate of 10 gigabits per second, so the tapped cables had the capacity, in theory, to deliver more than 21 petabytes a day”. GCHQ was able to spy on around a quarter of the world’s cables carrying Internet traffic, much of it from the US. Back in 2013, the Guardian reported that 300 analysts from GCHQ, and 250 from the NSA, had been assigned to sift through the flood of data. Once intercepted, the UK government uses “selectors” and “search criteria” to filter the content and – even more problematically – metadata it collects. These searches typically include finding all traffic to and from a particular location; Google search queries; purchases on Amazon; location data; and IP addresses.

All the intercepted data was placed in a single, massive database, code-named “Karma Police”. As The Intercept reported in 2015, drawing on other documents from Snowden:

One system builds profiles showing people’s web browsing histories. Another analyzes instant messenger communications, emails, Skype calls, text messages, cellphone locations, and social media interactions. Separate programs were built to keep tabs on “suspicious” Google searches and usage of Google Maps.

The surveillance is underpinned by an opaque legal regime that has authorized GCHQ to sift through huge archives of metadata about the private phone calls, emails, and internet browsing logs of Brits, Americans, and any other citizens — all without a court order or judicial warrant.

The initial legal challenge to this warrantless “bulk interception” – that is, mass surveillance – was made in July 2013 at the UK Investigatory Powers Tribunal (IPT). The IPT is “a court which investigates and determines complaints which allege that [UK] public authorities or law enforcement agencies have unlawfully used covert techniques and infringed our right to privacy, as well as claims against the security and intelligence agencies for conduct which breaches a wider range of our human rights.” The complaint was made by human rights organization Privacy International, along with nine other non-governmental organizations from around the world, including the American Civil Liberties Union.

However, in December 2014, the IPT held that both UK bulk interception and UK access to US bulk surveillance were lawful in principle. As a result, the ten human rights organizations filed an application to the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) challenging both of these decisions. The ECtHR has now issued its judgment, which is long and detailed. Privacy International has provided a good summary of the key points.

The ECtHR ruled that mass surveillance is not in itself a breach of human rights: it falls within a state’s “margin of appreciation in choosing how best to achieve the legitimate aim of protecting national security”. However, the lack of adequate oversight for GCHQ’s tapping of fiber-optic cables and analysis of the data it gathered, was a breach of human rights. The ECtHR was “not persuaded that the safeguards governing the selection of bearers [fiber-optic calbes] for interception and the selection of intercepted material for examination are sufficiently robust to provide adequate guarantees against abuse.” It also emphasised that what was “Of greatest concern, however, is the absence of robust independent oversight of the selectors and search criteria used to filter intercepted communications.”

Importantly, the court recognized that metadata can be even more revealing about our private lives than content, and criticized the lack of safeguards for its gathering and use by GCHQ. These flaws in the UK mass interception law led the judges to conclude it “is incapable of keeping the ‘interference’ [with privacy] to which is ‘necessary in a democratic society’.”

The ECtHR went on to criticize the lack of safeguards when intercepting and searching journalistic material. As a result, the Court said a blanket power to interfere with journalists’ communications, including with their sources, could have a broader “chilling effect … on the freedom of the press.” However, on one point the court sided with the UK government. It ruled that the intelligence sharing between the US and UK was compliant with the right to privacy.

The judgment concerned the UK’s Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act 2000, which was replaced by the Investigatory Powers Act 2016, as Privacy News Online reported at the time. However, the two laws have much in common, and legal commentators believe that many of the points made by the ECtHR would also apply to the later law, which will need to be revised to comply with the ruling. Similarly, it’s worth noting that this judgment is not just about the UK: it also provides interpretation of the European Convention on Human Rights for the 47 member States of the Council of Europe, all of which are parties to the Convention. This means that they should all be reviewing their surveillance laws to ensure they are compatible with the European Convention on Human Rights.

Although the ruling does not affect US citizens directly, the fact that GCHQ has been gathering Internet traffic worldwide, and sharing it with the NSA, means that there should in the future be greater oversight of such surveillance, and thus better privacy protection when people in the US go online.

All of these are welcome consequences of the ruling by the ECtHR. However, in an analysis of the latest decision, Theodore Christakis, Professor of International Law at the University Grenoble Alpes, cautions: “This was undoubtedly a victory for NGOs, but it was probably not a “great” one; in fact, it may even prove to be a pyrrhic victory.” The problem is that for all its unequivocal criticisms of GCHQ’s actions, the ECtHR explicitly accepts mass surveillance as a valid government activity: “It is clear that bulk interception is a valuable means to achieve the legitimate aims pursued, particularly given the current threat level from both global terrorism and serious crime.”

As Christakis points out, that is in stark contrast to the EU’s top court, the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU), which has ruled against the idea of mass surveillance. For example, in the 2015 decision that struck down the “Safe Harbor” agreement regulating data flows of personal information across the Atlantic, the CJEU declared: “legislation permitting the public authorities to have access on a generalised basis to the content of electronic communications must be regarded as compromising the essence of the fundamental right to respect for private life.”

The clash between the rulings of the top human rights court in Europe, and the CJEU means that the status of mass surveillance in the EU is now somewhat unclear. That’s another good reason for human rights organizations to bring legal challenges to the practice wherever it is being deployed, in order to ensure that “bulk interception” is always subject to laws with meaningful oversight, and that privacy is not being undermined in secret.

Featured image by TeleGeography.