Google’s “smart city” in Toronto: what it wanted, what it will now get – and why it’s still problematic for privacy

Earlier this year, Privacy News Online wrote about the latest news concerning plans to create a model “smart city” on Toronto’s waterfront. The company involved, Sidewalk Labs, is part of the Alphabet stable, along with Google. In an attempt to quell fears about privacy and other aspects of the plan, Sidewalk Labs released 1500 pages of documentation spelling out what it wanted to do in Toronto.

Since then, there have been a number of important developments. One is the leak of a confidential Sidewalk Labs document from 2016, which provides insights into the original vision. Sidewalk wanted to be given taxation powers, including the ability to impose property taxes. The 2016 document revealed that the company would create and control its own public services, including charter schools, special transit systems and a private road infrastructure. Also noteworthy is its desire for local policing powers similar to those granted to universities. Sidewalk’s vision included unique data identifiers for every person, business or object registered in the district, with the aim of creating a historical record of where things have been and where they are going. There would be a quid pro quo for sharing more data with Sidewalk:

The document describes a tiered level of services, where people willing to share data can access certain perks and privileges not available to others. Sidewalk visitors and residents would be “encouraged to add data about themselves and connect their accounts, either to take advantage of premium services like unlimited wireless connectivity or to make interactions in the district easier,” it says.

There are interesting parallels here with China’s social credit system, where people are rewarded with benefits or punished with restrictions, according to how much they cooperate with the authorities. Sidewalk Labs no longer talks about any of these aspirations, and the scheme has now been scaled back dramatically, from the original 190-acre plan to 12 acres. In an attempt to address privacy fears, the company has released yet another massive document, a 483-page Digital Innovation Appendix. As if that weren’t already too much information to digest easily, the Digital Innovation Appendix has its own appendix, which details Quayside Digitally Enabled Services. Lilian Radovac has gone through the latter spreadsheet, and found the following:

The services list states that Digital IDs will provide “interoperable access to public and private services through a unified delivery mechanism,” and specifically mentions “income verification” for affordable housing alongside things like parcel delivery and transit payment. This suggests that people who are eligible for the small number of below-market-rate units in the development would have to register for a Sidewalk authorized Digital ID to apply for them.

Despite these concerns, the project seems to be moving ahead. The vice president of innovation at Waterfront Toronto, the Canadian government agency responsible for development of the area, said Sidewalk’s latest 483-page document did “a good job of satisfying the information we need for the evaluation”, which will be completed in March next year. An open letter from Waterfront Toronto board chair mentions several changes that have helped convince the authority. One of the most important concerns personal data generated by the project. Waterfront Toronto is now taking control of this aspect, and has imposed additional conditions. It will be in charge of all digital governance and privacy matters, including interactions with its government stakeholders. In addition, the Urban Data Trust idea, mentioned previously on Privacy Internet News, has been dropped:

Sidewalk Labs agrees that personal information will be stored and processed in Canada, and would use commercially reasonable efforts to store and process non-personal data in Canada, has removed the expectation for creation of the proposed “Urban Data Trust”, and agrees to not use “Urban Data” as a term, and would instead rely on existing terminology and legal constructs.

This is one of the most problematic aspects of all “smart cities”. Since the latter are predicated on gathering huge amounts of data about people as they use public and private spaces within such areas, the key issue is who controls that data, and who has access to it. Toronto provides a useful testing ground for solutions to those issues. However, some are unconvinced by the whole idea. Writing on the Real Life site, Jathan Sadowski has a bleak vision of what “smart cities” really mean:

Sensors, cameras, and other networked surveillance systems gather intelligence through quasi-militaristic methods to feed another set of systems capable of deploying resources in response. In reality, the urban command centers — or, the sophisticated analytics software that create relational networks of data, like that produced by the CIA-funded Palantir — are built primarily for police, not planners, let alone the public.

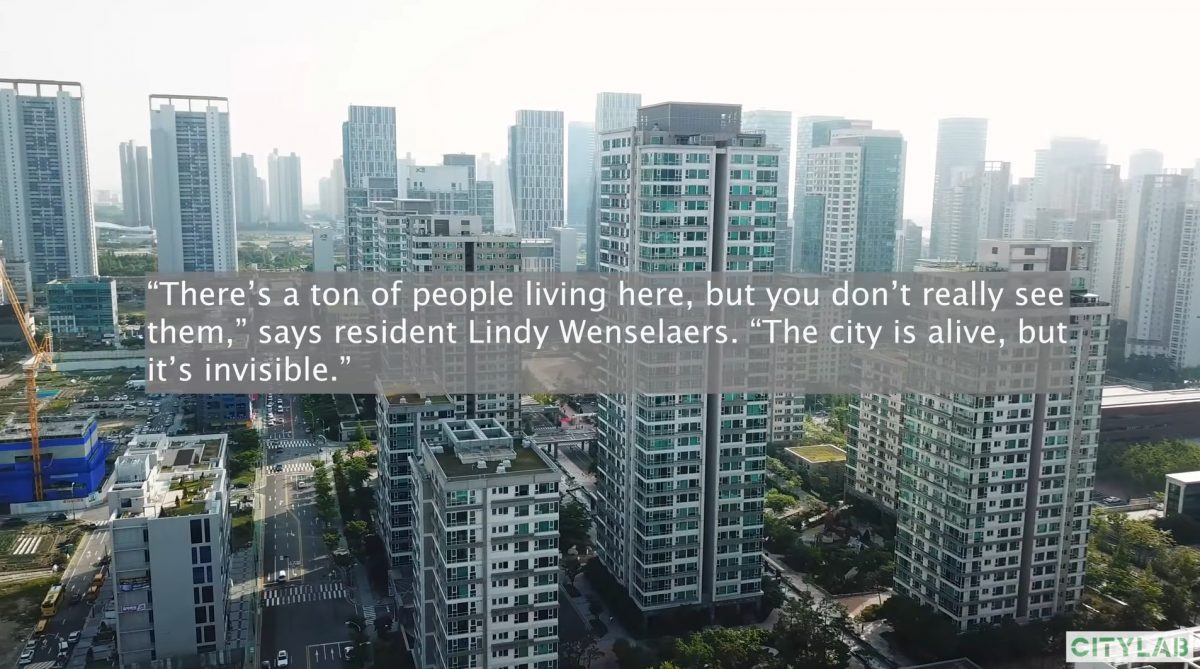

He also points to an earlier attempt to create a thoroughgoing digital urban environment. The city of Songdo, in South Korea, already has many of features that Sidewalk is promising for Toronto: pneumatic tubes send rubbish straight to underground waste facilities, and lights and heating in homes can be adjusted from a smartphone. But there’s a couple of things missing in Songdo: people, and a sense of community. Sidewalk will probably dodge those failings, for two reasons. It’s starting very small, and is subject to intense scrutiny by local communities, who are already deeply engaged. But the larger issue of personal data and what the real, long-term benefits of “smart” cities will be for people, remain.

Featured image by Citylab.